Taiz

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in Arabic. (September 2024) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

Taiz

ّتَعِز | |

|---|---|

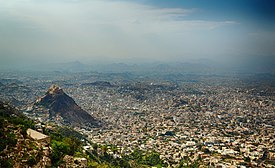

Overview of Taiz | |

| Coordinates: 13°34′44″N 44°01′19″E / 13.57889°N 44.02194°E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Janad |

| Governorate | Taiz |

| Elevation | 1,400 m (4,600 ft) |

| Population (2004)[1] | |

| • Total | 458,789 |

| • Estimate (2023)[1] | 940,600 |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (Yemen Standard Time) |

Taiz (Arabic: تَعِزّ, romanized: Taʿizz) is a city in southwestern Yemen. It is located in the Yemeni highlands, near the port city of Mocha on the Red Sea, at an elevation of about 1,400 metres (4,600 ft) above sea level. It is the capital of Taiz Governorate. As of 2023, the city has an estimated population of approximately 940,600 residents making it the third largest city in Yemen.[2]

History

[edit]

Medieval

[edit]The first reference to Taiz in historical sources dates back to the first half of the 12th century CE, when the sultan of the Sulayhid dynasty, Abdullah bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi, built the Al-Qahira Castle.[3] Taiz first became an urbanized area during the days of his brother Ali bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi.

The next historical reference to Taiz mentioned that Queen Arwa al-Sulayhi's minister, Prince Al-Mansur bin Al-Mufaddal bin Abi Al-Barakat, sold many of the country's castles and cities - except for the fortresses of Taiz and Sabr - to the ruler of Aden Al-Zari'i, the preacher Muhammad Ibn Saba, in exchange for one hundred thousand dinars.

Turan-Shah, the older brother of Saladin, ruled the city after he conquered Yemen in 1173 CE.[4] Turan-Shah built the citadel on the hill overlooking the old city.[5] In 1175 CE, Taiz was made the capital of Yemen as it was incorporated into dominions of the Ayyubid dynasty by Turan-Shah.

Taiz's expansion accelerated when the Rasulid dynasty, which ruled Yemen from 1229 to 1454, took over the city. The second Rasulid King, Almaddhafar (1288 CE), moved his kingdom's capital from Sanaa to Taiz, due to its proximity to Aden.[6] Taiz was said to have reached its golden age during the Rasulid dynasty, whose sultans spent lavishly on palaces, mosques, and madrassas.[3] Its neighborhoods also teemed with schools, guesthouses, markets, orchards, and lush gardens, and the city was considered to be a center for the study of the Shafi'i school of Islamic jurisprudence.

In 1332 Ibn Battutah visited Taiz and described it as one of the largest and most beautiful cities of Yemen:[7]

We went on ... to the town of Taʻizz, the capital of the king of Yemen, and one of the finest and largest towns in that country. Its people are overbearing, insolent, and rude, as is generally the case in towns where kings reside. Taʻizz is made up of three quarters; the first is the residence of the king and his court, the second, called ʽUdayna, is the military station, and the third, called al-Mahálib, is inhabited by the commonalty, and contains the principal market.[8]

In 1500, the capital was moved to Sana'a by the ruler of the Taharid dynasty. In 1516 Taiz came under Ottoman control.

1994 mass shooting

[edit]On March 25–26, 1994, a mass shooting took place in the city. A Yemeni killed eleven women and seven men, among them his wife and his mother, before he was arrested by police. When he was led away he managed to wrest the gun from a police officer and kill another four people, three of them police officers, before he himself was shot dead. A total of 23 people were killed, including the suspect.[9]

20th century

[edit]In 1918 the Ottomans lost Taiz to the newly independent Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen.

Taiz remained a walled city until 1948, when Imam Ahmed made it the second capital of Yemen, allowing for expansion beyond its fortified wall.[10] In the 1960s, the first purified water system in Yemen was opened in Taiz. In 1962, state administrations moved back to Sana'a.

Yemeni uprising and war

[edit]During the Yemeni Revolution fighting in Taiz resulted in anti-government forces seizing control of the city from president Ali Abdullah Saleh.

As part of the 2015 Yemeni Civil War, on 22 March 2015, the Houthis and forces loyal to former president Ali Abdullah Saleh took the city in the aftermath of their coup d'état in Sanaa.[11] The city became the site of a military confrontation between Houthis and the forces loyal to Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi. The city was effectively under siege and the United Nations warned of an "extreme and irreversible" food shortage if fighting continued.[12] In August 2015, Yemeni Member of Parliament Muhammad Muqbil Al-Himyari reported Houthi attacks on civilians in Taiz and appealed for help on Suhail TV (Yemen).[13][14]

The 2015 confrontation expanded into a military campaign for control of this strategic city.[15] Despite ceasefires and prisoner swaps, the battle continues to this day and the city has been described as a "volatile front line."[16] The frontline runs through the city from east to west, and journeys across the frontline that once took 5 minutes now take 5 hours.[17] Once known as the "cultural capital of Yemen", the war has bestowed a new name on Taiz: "city of snipers".[15][17]

As of 2018, at least seven journalists had been killed in Taiz since the start of the war.[18]

The fighting has also devastated Taiz's architectural heritage: Cairo Citadel was damaged by airstrikes in 2015, and the Taiz Museum was shelled in 2016, causing its manuscripts to be destroyed.[3]

Geography

[edit]Climate

[edit]Taiz has a hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification: BSh), bordering both a humid subtropical climate (Cwa) and a tropical savanna climate (Aw). The average daily temperature high during August is 32.5 °C (90.5 °F). Annual rainfall of Taiz is around 660 millimetres (26 in), but on Jabal Sabir it is probably around 1,000 millimetres (39.4 in) per year.

| Climate data for Taiz | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 24.3 (75.7) |

26.4 (79.5) |

27.9 (82.2) |

28.3 (82.9) |

29.0 (84.2) |

31.3 (88.3) |

32.5 (90.5) |

31.7 (89.1) |

31.3 (88.3) |

31.1 (88.0) |

27.6 (81.7) |

26.1 (79.0) |

29.0 (84.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 17.7 (63.9) |

19.9 (67.8) |

22.1 (71.8) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.6 (78.1) |

26.4 (79.5) |

25.4 (77.7) |

24.6 (76.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

21.7 (71.1) |

20.0 (68.0) |

22.9 (73.2) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | 11.1 (52.0) |

13.3 (55.9) |

16.3 (61.3) |

18.8 (65.8) |

19.5 (67.1) |

19.9 (67.8) |

20.2 (68.4) |

19.1 (66.4) |

17.8 (64.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

15.7 (60.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

16.9 (62.4) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 9 (0.4) |

12 (0.5) |

37 (1.5) |

68 (2.7) |

89 (3.5) |

73 (2.9) |

60 (2.4) |

89 (3.5) |

110 (4.3) |

91 (3.6) |

17 (0.7) |

5 (0.2) |

660 (26.2) |

| Source 1: Hydrological Sciences[19] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Journal of Environmental Protection[20] | |||||||||||||

Landmarks

[edit]

The city has many old quarters, with houses that are typically built with brown bricks, and mosques that are usually whitewashed. The most famous mosques in the city are the Ashrafiya, the Mua'tabiya Mosque, and the Mudhaffar Mosque. Other landmarks include Cairo Citadel, which looms above the city from the south, and the governor's palace, which rests on top of a mountain spur 450 m (1,480 ft) above the city centre. Taiz is also home to one of the best-known mountains in Yemen, Jabal Saber,[21] almost 3,000 metres (1.9 miles) above sea level), which affords panoramic views over the city.

Economy

[edit]Historically, the mountainous city of Taiz was known for coffee production. The Mocha coffee produced in Taiz was considered some of the finest in the region in the early 20th century.[22] Today, coffee remains a major part of the economy but mango, pomegranate, citrus, banana, papai, vegetables, cereals, onions, and qat are also grown in the surrounding landscapes.[23] Taiz is also known for its cheese. It is produced in rural areas like Araf, Awshaqh, Akhuz, Bargah, Barah, Jumah, Mukyas, Suayra, Kamb and Hajda and sold in Bab al-Kabeer and Bab Musa markets.[24][25] Industries in the city of Taiz include cotton-weaving, tanning and jewelry production.

However, since the outbreak of the civil war in 2015, Taiz's economy has been devastated by the fighting and the city's siege by Houthi rebels. Many goods are in short supply, and must be smuggled in across steep mountain roads to avoid sniper fire.[18]

Transport

[edit]Taiz has many road connections with the rest of the country. However, as of January 2023, most roads to and from Ta'iz are controlled by the Houthis, who are besieging the city as part of the Yemeni Civil War.[17] The city is served by Ta'izz International Airport.[26] With the closing of this airport due to the civil war, the only way into and out of the city is via cars or small buses that goes through a longer and less serviced roads than the normal roads before the war. However, There was an agreement recently towards open roads in Taiz that will save time and effort for people to go in and out the city.[27]

Zoo

[edit]Like Sana'a Zoo, this zoo held fauna caught in the wild, such as the Arabian leopard, as well as exotic animals such as African lions and gazelles.[28] Due to the civil war, however, many of the animals held at the zoo have become sick or died due to lack of food.[29]

Notable people

[edit]- Tawakkol Karman, Yemeni Nobel Laureate, journalist, politician, and human rights activist.[30]

- Amat Al Alim Alsoswa, journalist and Yemen's first female ambassador

- Abdel Karim al-Khaiwani, politician and human rights activist

- Bushra al-Maqtari, writer and activist

- Ali al-Muqri, novelist

- Maeen Abdulmalik Saeed, Yemeni prime minister

- Hisham Sharaf, Yemeni minister of foreign affairs

- Zayd Mutee' Dammaj, writer

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "Taiz Population 2023". worldpopulationreview.com. Archived from the original on 2023-08-14. Retrieved 2023-08-14.

- ^ a b c "Old City of Ta'izz". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ Lane-Poole, Stanley (2013-10-03). A History of Egypt: Volume 6, In the Middle Ages. Cambridge University Press. p. 197. ISBN 9781108065696. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ Steven C. Caton: Yemen. ABC-CLIO, 2013, p.52

- ^ Mackintosh-Smith, Tim (2014-06-03). Yemen: The Unknown Arabia. The Overlook Press. p. 305. ISBN 9781468309980. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ First Encyclopaedia of Islam: 1913-1936. BRILL. 1993. p. 626. ISBN 9-0040-9796-1. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2020-09-26.

- ^ H.A.R. Gibb, translator, Ibn Battúta: Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354, London, 1929, p. 108-109 Archived 2024-08-14 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Künzi, Hans P. (2001), "Neue Zürcher Zeitung", Verleger • Humanist Homme de Lettres, Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, pp. 61–62, doi:10.1007/978-3-662-38087-1_13, ISBN 978-3-662-37346-0, archived from the original on 2024-08-14, retrieved 2024-06-25

- ^ Gibb, Hamilton Alexander Rosskeen (1998). The Encyclopaedia of Islam: TAHRIR-TARDJAMA. Brill. p. 118. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2024-08-14.

- ^ "Rebels Seize Key Parts of Yemen's Third-Largest City, Taiz". The New York Times. 22 March 2015. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 22 March 2015.

- ^ "UN warns of 'extreme' and 'irreversible' food shortage in Taiz". Al Jazeera. Al Jazeera. 30 October 2015. Archived from the original on 4 November 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2015.

- ^ "#5060 - Yemeni MP Muhammad Muqbil Al-Himyari Breaks Down in Tears When Discussing Situation in Taiz, Yemen Suhail TV". Memritv. August 24, 2015. Archived from the original on September 5, 2015. Retrieved September 4, 2015.

- ^ "Transcript #5060 - Yemeni MP Muhammad Muqbil Al-Himyari Breaks Down in Tears When Discussing Situation in Taiz, Yemen". Memritv. August 24, 2015.

- ^ a b Waguih, Asmaa (2016-07-12). "The Battle Over Yemen's Cultural Capital Continues". Foreign Affairs: America and the World. ISSN 0015-7120. Archived from the original on 2022-05-22. Retrieved 2019-04-13.

- ^ "Warring Yemen parties carry out prisoner swap in front-line Taiz". Reuters. 2019-12-19. Archived from the original on 2022-01-21. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- ^ a b c Doucet, Lyse (2020-03-15). "In the rubble of Taiz, all roads to a normal life are blocked". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ^ a b Nasser, Afrah. "From the front lines of Yemen's lawless Taiz". Atlantic Council. Archived from the original on January 16, 2023. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "Rainfall and Runoff in Yemen" (PDF). Hydrological Sciences. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-12. Retrieved 2013-03-18.

- ^ Al-Buhairi, Mahyoub H.; "Analysis of Monthly, Seasonal and Annual Air Temperature Variability and Trends in Taiz City - Republic of Yemen"; in Journal of Environmental Protection, 2010 (1); pp. 401-409

- ^ Hestler, Ann; Spilling, Jo-Ann (2010). "1: Introduction". Yemen. New York City: Cavendish. p. 17. ISBN 978-0-7614-4850-1. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ Prothero, G.W. (1920). Arabia. London: H.M. Stationery Office. p. 83. Archived from the original on 2016-12-27. Retrieved 2013-09-09.

- ^ Yementourism.com, http://www.yementourism.com/services/touristguide/detail.php?ID=2044 Archived 2016-04-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Say Yemeni Cheese!". Archived from the original on 2020-11-10. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ^ "Homepage". Archived from the original on 2019-07-29. Retrieved 2019-07-29.

- ^ El Mallakh, Ragaei (2014). "Infrastructure". The Economic Development of the Yemen Arab Republic (RLE Economy of Middle East). Routledge. ISBN 978-1-3175-9810-7. Archived from the original on 2024-08-14. Retrieved 2020-12-17.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2023-05-31. Retrieved 2023-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ De Haas van Dorsser, F. J.; Thowabeh, N. S.; Al Midfa, A. A.; Gross, Ch. (2001), Health status of zoo animals in Sana'a and Ta'izz, Republic of Yemen (PDF), Sana'a, Yemen: Breeding Centre for Endangered Arabian Wildlife, Sharjah; Environment Protection Authority, pp. 66–69, archived (PDF) from the original on 2019-05-05, retrieved 2019-05-05

- ^ Raghavan, Sudarsan (June 10, 2016). "'Imagine living and dying in such a small space': Zoo workers in Yemen are struggling to feed starving animals". Washington Post. Archived from the original on October 14, 2021. Retrieved January 15, 2023.

- ^ "The Nobel Peace Prize 2011". NobelPrize.org. Archived from the original on 2021-01-28. Retrieved 2023-01-30.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to Ta'izz at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ta'izz at Wikimedia Commons

- ArchNet.org. "Taizz". Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA: MIT School of Architecture and Planning. Archived from the original on 2008-05-05.