Robert Barnwell Rhett

Robert Barnwell Rhett | |

|---|---|

| |

| Deputy to the Provisional C.S. Congress from South Carolina | |

| In office February 4, 1861 – February 18, 1862 | |

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Position abolished |

| United States Senator from South Carolina | |

| In office December 18, 1850 – May 7, 1852 | |

| Preceded by | Robert Barnwell |

| Succeeded by | William de Saussure |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from South Carolina | |

| In office March 4, 1837 – March 3, 1849 | |

| Preceded by | William Grayson |

| Succeeded by | William Colcock |

| Constituency | 2nd district (1837–43) 7th district (1843–49) |

| 8th Attorney General of South Carolina | |

| In office November 29, 1832 – March 4, 1837 | |

| Governor | Robert Hayne George McDuffie Pierce Butler |

| Preceded by | Hugh S. Legaré |

| Succeeded by | Henry Bailey |

| Member of the South Carolina House of Representatives from St. Bartholomew's Parish | |

| In office November 27, 1826 – November 29, 1832 | |

| Personal details | |

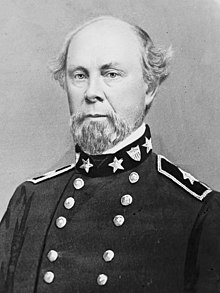

| Born | Robert Barnwell Smith December 21, 1800 Beaufort, South Carolina |

| Died | September 14, 1876 (aged 75) St. James Parish, Louisiana |

| Resting place | Magnolia Cemetery, Charleston, South Carolina |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Other political affiliations | Southern National Party |

| Relations | R. Barnwell Rhett Jr. (son), Alfred M. Rhett (son), Alicia Rhett (great-granddaughter) |

| Occupation | Politician, lawyer, planter, and newspaper publisher |

Robert Barnwell Rhett (born Robert Barnwell Smith; December 21, 1800 – September 14, 1876) was an American politician who served as a deputy from South Carolina to the Provisional Confederate States Congress from 1861 to 1862, a member of the US House of Representatives from South Carolina from 1837 to 1849, and US Senator from South Carolina from 1850 to 1852. As a staunch supporter of slavery and an early advocate of secession, he was a "Fire-Eater", nicknamed the "father of secession".

Rhett published his views through his newspaper, the Charleston Mercury.[1]

His son Alfred M. Rhett commanded a battery at Fort Moultrie at the time of the bombardment of Fort Sumter.[2]

Early life

[edit]Rhett was born Robert Barnwell Smith in Beaufort, South Carolina, United States. He later studied law.

Rhett was of English ancestry. On his mother's side, he was related to U.S. Representative Robert Barnwell (his great-uncle) and Senator Robert Woodward Barnwell (son of Robert). A cousin of the Barnwells was the wife of Alexander Garden.[3]

Early career

[edit]Rhett was a member of the South Carolina legislature from 1826 until 1832, and was extremely pro-slavery in his views. At the end of the Nullification Crisis in 1833, he told the South Carolina Nullification Convention:

A people, owning slaves, are mad, or worse than mad, who do not hold their destinies in their own hands.[4]

In 1832, Rhett became South Carolina's Attorney General, serving until 1837. He was then elected a US Representative and served until 1849. In 1838, he changed his last name from Smith to that of a prominent colonial ancestor, Colonel William Rhett.

Rhett objected vehemently to the protectionist Tariff of 1842.

Support for secession

[edit]On July 31, 1844, Rhett launched the Bluffton Movement, which called for South Carolina to return to nullification or else declare secession. It was soon repudiated by more moderate South Carolina Democrats, including even Senator John C. Calhoun, who feared it would endanger the presidential candidacy of James K. Polk.

Rhett opposed the Compromise of 1850 as against the interests of the slave-holding South. He joined fellow Fire-Eaters at the Nashville Convention of 1850, which failed to endorse his aim of secession for the whole South. After the Nashville Convention, Rhett, William Lowndes Yancey, and a few others met in Macon, Georgia on August 21, 1850, and formed the short-lived Southern National Party. In December 1850, he was appointed to be a U.S. Senator to complete the term left by the death of Calhoun. He continued to advocate secession in response to the Compromise, but in 1852, South Carolina refrained from declaring secession and merely passed an ordinance declaring a state's right to secede. Disappointed, he resigned his Senate seat.

He continued to express his fiery secessionist sentiments through the Charleston Mercury, now edited by his son, Robert Barnwell Rhett Jr.

The 1860 Democratic National Convention met in Charleston, South Carolina and a large bloc of Southern delegates walked out when the platform was insufficiently pro-slavery. That led to the division of the party and separate Northern and Southern nominees for president, which practically guaranteed the election of an anti-slavery Republican, which in turn triggered declarations of secession in seven states. During the 1860 presidential campaign, a widely credited report in the Nashville Patriot said that the outcome was the intended result of a conspiracy by Rhett, Yancey, and William Porcher Miles hatched at the Southern Convention in Montgomery, Alabama in May 1858.[5] One 20th-century historian called the scheme the work of "Rhett–Yancey–Keitt extremists."[6]

Confederate States

[edit]

After the election of the Republican Party's candidate, Abraham Lincoln, Rhett was elected to the South Carolina Secession Convention, which declared secession in December. He was chosen as deputy from South Carolina to the Provisional Confederate States Congress in Montgomery. He was one of the most active deputies and was the chairman of the committee that reported the Confederate States Constitution. He was then elected to the Confederate House of Representatives. He received no higher office in the Confederate government and returned to South Carolina. During the rest of the Civil War, he sharply criticized the policies of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

In October 1865, Confederate military officer P.G.T. Beauregard wrote to Rhett encouraging him to resume publication of the Charleston Mercury "to help in re-establishing the truths of History. It will be difficult, even for many of our own people, to believe that so glorious a cause as the one we fought for should have been sacrificed by the prejudices & want of judgment & foresight of one man [Jefferson Davis]! Yet such was the fact, according to my most deliberate opinion."[7]

Death

[edit]Rhett struggled with skin cancer for many years, including a "cancerous growth on his nose which terribly disfigured him and also affected his general health in the years after the war."[7] After the war, Rhett settled in Louisiana. He died in St. James Parish, Louisiana, and is interred at Magnolia Cemetery in Charleston, South Carolina.

Legacy

[edit]The Robert Barnwell Rhett House in Charleston was declared a National Historic Landmark in 1973.[8][9]

See also

[edit]- List of slave owners

- List of United States representatives from South Carolina

- List of United States senators from South Carolina

References

[edit]Notes

- ^ The Secession Archived March 6, 2017, at the Wayback Machine Charleston News and Courier. December 18, 1960

- ^ Island, Mailing Address: 1214 Middle Street Sullivan's; Us, SC 29482 Phone:577-0242 Contact. "Alfred M. Rhett - Fort Sumter and Fort Moultrie National Historical Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Davis, William C. (2001). Rhett: The Turbulent Life and Times of a Fire-Eater. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-57003-439-8.

- ^ Freehling, William W. Prelude to Civil War: The Nullification Crisis in South Carolina 1816-1836, p. 297.

- ^ Allan Nevins, The War for the Union, vol. 1: The Improvised War, 1861-1862 (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1959), p. 28.

- ^ Roseboom, Eugene H.; Crenshaw., Ollinger (September 1947). "The Slave States in the Presidential Election of 1860". The Mississippi Valley Historical Review. 34 (2): 307. doi:10.2307/1896188. JSTOR 1896188.

- ^ a b "Caroliniana Society Annual Gifts Report - April 2010". University South Caroliniana Society. University of South Carolina Libraries. April 1, 2010.

- ^ "Robert Barnwell Rhett House". National Historic Landmark summary listing. National Park Service. Archived from the original on June 6, 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2008.

- ^ Levy, Benjamin (January 29, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination" (pdf). National Park Service.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) and Accompanying two photos, exterior, from 1973 (32 KB)

Further reading

- Rhett, Robert Barnwell (2000). Davis, William C. (ed.). A Fire-Eater Remembers: The Confederate Memoir of Robert Barnwell Rhett. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press. ISBN 978-1-57003-348-3.

- Scarborough, William K., "Propagandists for Secession: Edmund Ruffin of Virginia and Robert Barnwell Rhett of South Carolina", South Carolina Historical Magazine 112 (July–Oct. 2011), 126–38.

- White, Laura A. (1931) Robert Barnwell Rhett: Father of Secession

External links

[edit]- United States Congress. "Robert Barnwell Rhett (id: R000184)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- Works by or about Robert Barnwell Rhett at the Internet Archive

- 1800 births

- 1876 deaths

- 19th-century American newspaper publishers (people)

- 19th-century American politicians

- 19th-century American planters

- Democratic Party members of the United States House of Representatives from South Carolina

- Democratic Party United States senators from South Carolina

- Deputies and delegates to the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States

- Members of the Confederate House of Representatives from South Carolina

- Democratic Party members of the South Carolina House of Representatives

- Nullification crisis

- People from Beaufort, South Carolina

- Signers of the Confederate States Constitution

- Signers of the Provisional Constitution of the Confederate States

- South Carolina attorneys general

- South Carolina lawyers

- Fire-Eaters

- Burials at Magnolia Cemetery (Charleston, South Carolina)

- United States senators who owned slaves

- Members of the United States House of Representatives who owned slaves

- University of South Carolina Beaufort alumni