Thomas Tenison

Thomas Tenison | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of Canterbury | |

Portrait by Simon Dubois | |

| Church | Church of England |

| Diocese | Canterbury |

| In office | 1695–1715 |

| Predecessor | John Tillotson |

| Successor | William Wake |

| Orders | |

| Consecration | 10 January 1692 by John Tillotson |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 September 1636 Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, England |

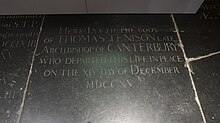

| Died | 14 December 1715 (aged 79) London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Denomination | Anglican |

| Spouse | Anne Love |

| Education | Norwich School |

| Alma mater | Corpus Christi College, Cambridge |

Thomas Tenison (29 September 1636 – 14 December 1715) was an English church leader, Archbishop of Canterbury from 1694 until his death. During his primacy, he crowned two British monarchs.

Life

[edit]He was born at Cottenham, Cambridgeshire, the son and grandson of Anglican clergymen, who were both named John Tenison; his mother was Mercy Dowsing. He was educated at Norwich School, going on to Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, as a scholar on Archbishop Matthew Parker's foundation. He graduated in 1657, and was chosen fellow in 1659.[2] For a short time he studied medicine, but in 1659 was privately ordained. As curate of St Andrew the Great, Cambridge from 1662, he set an example by his devoted attention to the sufferers from the plague. In 1667 he was presented to the living of Holywell-cum-Needingworth, Huntingdonshire, by the Earl of Manchester, to whose son he had been tutor, and in 1670 to that of St Peter Mancroft, Norwich.[3]

In 1680 he received the degree of Doctor of Divinity, and was presented by King Charles II to the important London church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. Tenison, according to Gilbert Burnet, "endowed schools including Archbishop Tenison's School, Lambeth, founded in 1685 and Archbishop Tenison's School, Croydon, founded in 1714, set up a public library, and kept many curates to assist him in his indefatigable labours". Being a strenuous opponent of the Church of Rome, and "Whitehall lying within that parish, he stood as in the front of the battle all King James's reign". In 1678, in a Discourse of Idolatry, he condemned the heathenish idolatry practised in the Church of Rome, and in a sermon which he published in 1681 on Discretion in Giving Alms was attacked by Andrew Poulton, head of the Jesuits in the Savoy. Tenison's reputation as an enemy of Romanism led the Duke of Monmouth to send for him before his execution in 1685, when Bishops Thomas Ken and Francis Turner refused to administer holy communion; but, although Tenison spoke to him in "a softer and less peremptory manner" than the two bishops, he was, like them, not satisfied with the sufficiency of Monmouth's penitence.[3]

Under King William III, Tenison was in 1689 named a member of the ecclesiastical commission appointed to prepare matters towards a reconciliation of the Dissenters, the revision of the liturgy being specially entrusted to him. A sermon he preached on the commission was published the same year.[3]

He strongly supported, at least in public, the Glorious Revolution, though not without some private misgivings, especially concerning the ejection of Archbishop William Sancroft and the other "non-juring" bishops. Henry Hyde, 2nd Earl of Clarendon in his diary records some frank remarks made by Tenison on this subject at a dinner party in 1691:

That there had been irregularities in our settlement; that it was wished that things had been otherwise, but that we were now to make the best of it, and support this government as it was, for fear of a worse.

He preached a funeral sermon for Nell Gwyn in 1687, in which he represented her as truly penitent – a charitable judgment that did not meet with universal approval. The general liberality of Tenison's religious views won him royal favour, and, after being made Bishop of Lincoln in 1691, he was promoted to Archbishop of Canterbury in December 1694.[3]

Archbishop of Canterbury

[edit]He attended Queen Mary during her last illness and preached her funeral sermon in Westminster Abbey. In 1695, when William went to take command of the army in the Netherlands, Tenison was appointed one of the seven lords justices to whom his authority was delegated.[3] After Mary's death, Tenison was one of those who persuaded the King that his long and bitter quarrel with her sister Anne must be ended, as it had weakened the authority of the Crown.[4] He was sworn in as a member of the Privy Council of England in 1695 upon his appointment as Archbishop of Canterbury. This gave him the Honorific Title "The Right Honourable" for Life.

Under Queen Anne

[edit]Along with Gilbert Burnet, he attended King William on his deathbed. He crowned William's successor, Queen Anne, but during her reign was in very little favour at court:[5] the Queen thought that he inclined too much to the Low Church, and clashed repeatedly with him over her sole right to appoint bishops. She entirely ignored his wishes when she appointed Sir Jonathan Trelawny, 3rd Baronet, as Bishop of Winchester: when he tried to remonstrate, the Queen cut him short with the cold remark that "the matter was decided." Only with great difficulty did he persuade her to appoint his nominee William Wake, as Bishop of Lincoln.[6]

Increasingly he lost influence to John Sharp, Archbishop of York, whom the Queen found far more congenial.[7] He was a commissioner for the Union with Scotland in 1706; but in the last years of the Queen's reign he was very much a secondary political figure, and from September 1710, though he was still nominally a member of the Cabinet, ceased to attend its meetings.[8] A strong supporter of the Hanoverian succession, who shocked many by referring to Anne's death as a blessing,[9] he was one of three officers of state to whom, on the death of Anne, was entrusted the duty of appointing a regent till the arrival of George I, whom he crowned on 20 October 1714.[3] For the last time at the coronation of an English monarch, the Archbishop asked if the people accepted their new King: the witty Catherine Sedley, former mistress of James II, remarked: "Does the old fool think we will say no?". Tenison died in London a year later. He was instrumental in the last years of his life in the literary executorship of Sir Thomas Browne's manuscript writings known as Christian Morals.

Other works

[edit]Besides the sermons and tracts above mentioned, and various others on the "Popish" controversy, Tenison was the author of The Creed of Mr Hobbes Examined (1670) and Baconia, or Certain Genuine Remains of Lord Bacon (1679). He was one of the founders of the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel.[10]

Family

[edit]He married Anne, daughter of Richard Love; but died without issue.[11] Edward Tenison (1673–1735) LL.B (Cantab.), his cousin, became Bishop of Ossory (Ireland) (1730/1731-1735).[12][13] Another relative, Richard Tennison (1642–1705), became Bishop of Meath. Thomas is said to have advanced Richard in his career: in his will he left legacies to all of Richard's five sons.

In appearance, he was described as a large, brawny, "hulking" figure, very strong when young but afflicted with gout in later life.[14]

Armorials

[edit]The personal coat of arms of Archbishop Tenison consists of the arms of the see of Canterbury impaled with the Tenison family arms. The former, placed on the dexter side of honour, are blazoned as: Azure, an archiepiscopal cross in pale or surmounted by a pall proper charged with four crosses patee fitchee sable. The arms of Tenison, placed on the sinister side of the escutcheon are blazoned as: Gules, a bend engrailed argent voided azure, between three leopard's faces or jessant-de-lys azure. In standard English: a red field bearing a white (or silver) diagonal band with scalloped edges, and a narrower blue band running down its centre. This lies between three gold heraldic lion's faces, each of which is pierced by a fleur-de-lys entering through the mouth.

These arms are a difference, or variant, of the mediaeval arms of the family of Denys of Siston, Gloucestershire, and may have been adopted by the Tenison family because its name signifies "Denys's or Denis's son". The arms were originally those of the Norman de Cantilupe family, whose feudal tenants the Denys family probably were in connection with Candleston Castle in Glamorgan. St Thomas Cantilupe (died 1282), bishop of Hereford, gave a reversed (i.e. upside down) version of the Cantilupe arms to the see of Hereford, which uses them to this day. A version of the Denys arms was also adopted by the family of the poet laureate Alfred, Lord Tennyson, not known to have been a descendant of Archbishop Thomas Tenison.

Suspected discovery of his coffin

[edit]

In 2016, during the refurbishment of the Garden Museum,[15] which is housed at the medieval church of St Mary-at-Lambeth,[16] 30 lead coffins were found; one with an archbishop's red and gold mitre on top of it.[17] Two archbishops were identified from nameplates on their coffins; with church records revealing that a further three archbishops, including Tenison, were likely to be buried in the vault.[18]

See also

[edit]- Archbishop Tenison's School, Croydon

- Archbishop Tenison's School, Lambeth

- List of Archbishops of Canterbury

Notes

[edit]- ^ Burkes General Armory, 1884

- ^ "Tenison, Thomas (TNY653T)". A Cambridge Alumni Database. University of Cambridge.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911, p. 617.

- ^ Gregg, Edward Queen Anne Yale University Press 1980 p.102

- ^ Gregg p.206

- ^ Somerset, Anne Queen Anne Harper Press 2012 p.224

- ^ Gregg p.146

- ^ Gregg p.141

- ^ Somerset p.540

- ^ Chisholm 1911, pp. 617–618.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ . Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

- ^ George Stanhope, A Letter from the Prolocutor to the Reverend Dr. Edward Tenison, Archdeacon of Carmarthen, 1718

- ^ Somerset p.224

- ^ Museum web-site

- ^ Church of St Mary, Lambeth British History on-line

- ^ Times on-line

- ^ "Remains of five 'lost' Archbishops of Canterbury found". BBC. 16 April 2017.

References

[edit]- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Tenison, Thomas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 26 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 617–618.

- Hutton, William Holden (1898). . In Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 56. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Marshall, William. "Tenison, Thomas (1636–1715)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/27130. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

Further reading

[edit]- Edward Carpenter, Thomas Tenison, Archbishop of Canterbury: His Life and Times (SPCK, 1948).

External links

[edit]- 1636 births

- 1715 deaths

- 17th-century Anglican archbishops

- 17th-century Anglican theologians

- 17th-century Church of England bishops

- 18th-century Anglican archbishops

- 18th-century Anglican theologians

- Alumni of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

- Archbishops of Canterbury

- Bishops of Lincoln

- Burials at St Mary-at-Lambeth

- Chancellors of the College of William & Mary

- Founders of English schools and colleges

- Members of the Privy Council of England

- People educated at Norwich School

- People from Cottenham