Yan (state)

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2023) |

Yan 燕 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11th century BC–222 BC | |||||||

| |||||||

| Status | Kingdom/Principality | ||||||

| Capital | Ji (蓟) Xiadu | ||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||

| Historical era | Zhou dynasty | ||||||

• Established | 11th century BC | ||||||

• Conquered by Qin | 222 BC | ||||||

| Currency | knife money spade money other ancient Chinese coinage | ||||||

| |||||||

| Yan | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

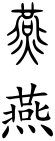

"Yān" in ancient seal script (top) and modern (bottom) Chinese characters | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese | 燕 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Yān | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yan (Chinese: 燕; pinyin: Yān; Old Chinese pronunciation: *ʔˤe[n]) was an ancient Chinese state during the Zhou dynasty.[2][3] Its capital was Ji (later known as Yanjing and now Beijing).[4] During the Warring States period, the court was also moved to another capital at Xiadu at times.[5]

The history of Yan began in the Western Zhou in the early first millennium BC. After the authority of the Zhou king declined during the Spring and Autumn period in the 8th century BC, Yan survived and became one of the strongest states in China. During the Warring States period from the 5th to 3rd centuries BC, Yan was one of the last states to be conquered by the armies of Qin Shihuang: Yan fell in 222 BC, the year before the declaration of the Qin Empire. Yan experienced a brief period of independence after the collapse of the Qin dynasty in 207 BC, but it was eventually absorbed by the victorious Han.

During its height, Yan stretched from the Yellow River to the Yalu River and from the mountains of Shanxi to the Liaodong Peninsula. As the northernmost of all the Chinese states during this time period, Yan faced incursions from steppe nomads and as such, built great walls.

History

[edit]According to Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian, King Wu of Zhou deposed King Zhou of Shang at the Battle of Muye (c. 1046 BC) and conferred titles to nobles within his domain, including the rulers of the Yan.[6]

In the 11th century BC, Yan's capital was based in what is now Liulihe Township, Fangshan District, Beijing, where a large walled settlement and over 200 tombs of nobility have been unearthed.[7] Among the most significant artifacts from the Liulihe Site is a bronze ding with inscriptions that recount the journey of the eldest son of the Duke of Yan, who delivered offerings to the King of Zhou in present-day Xi'an and was awarded a position in the king's court.

Some time during the 7th century BC in the late Western Zhou or early Eastern Zhou, Yan absorbed the State of Ji, a smaller kingdom to the north and moved its capital to that of Ji in modern-day Xicheng District, Beijing.

To the south, the bordering states of Zhao and Qi were Yan's main rivals. The mountainous border in the west between Zhao and Yan became the area in which their armies often clashed. Despite this, the war between Zhao and Yan usually dragged on into a stalemate, requiring the help of other kingdoms to conclude.

At the turn of the 3rd century BC, General Qin Kai launched a series of campaigns against the Donghu and Gojoseon, expanding the kingdom's frontiers nearly one thousand kilometers east to northwestern Korean Peninsula. A Great Wall was constructed on Yan's new northern borders, and five commanderies, Shanggu, Yuyang, Youbeiping, Liaoxi and Liaodong, were subsequently established for the defense against the Donghu.

The Central Plains states seemed to hold Yan culture and other peripheral states like Qin in low regard. Archaeological discoveries in the state of Yan have uncovered ornaments that, while inscribed with Chinese writing, were close in style to that of the northern nomadic tribes. The currency of Yan was crafted into the shape of a knife, a form closely associated with the nomads. This form of currency might have been specially made for trade with the nomads, demonstrating the importance of commercial relations with them.[8]

The strongest opposition came from the Qi, one of the strongest states in China. A succession crisis started in Yan in 325 BC when king Zikuai symbolically resigned his throne in favor of his minister Zizhi to prove his humility; the minister took advantage and seized power.[9] While this crisis happened, in 314 BC Qi invaded and in a little over several months practically conquered the country. However, due to the misconduct of Qi troops during the conquest of Yan a revolt eventually drove them away and the borders of Yan were restored. Yan's new king, King Zhao of Yan then plotted with the states of Zhao, Qin, Han and Wei for a joint expedition against Qi. Led by the brilliant tactician Yue Yi, it was highly successful and within a year most of Qi's seventy walled cities had fallen, with the exception of Zimu and Lu. However, with the death of King Zhao and the expulsion of Yue Yi to Zhao by the new king, King Wei of Yan, General Tian Dan managed to recapture all of the cities from the 5 kingdoms.

Despite the wars, Yan survived through the Warring States period. In 227 BC, with Qin troops on the border after the collapse of Zhao, Crown Prince Dan sent an assassin named Jing Ke to kill the king of Qin (later Qin Shi Huang), hoping to end the Qin threat. The mission failed, with Jing Ke dying at the hands of the King of Qin in Xianyang.

Surprised and enraged by such a bold act, the king of Qin called on Wang Jian to destroy Yan. Crushing the bulk of the Yan army at the frozen Yi River, Ji fell the following year and the ruler, King Xi, fled to the Liaodong Peninsula.

In 222 BC, Liaodong fell as well, and Yan was overrun by Qin. Yan was the third to last state to fall, and with its destruction the fates of the remaining two kingdoms were sealed. In 221 BC, Qin conquered all of China, ending the Warring States period and founding the Qin dynasty.

Post-Qin interregnum

[edit]In 207 BC, the Qin dynasty collapsed and China resumed a state of civil war. King Wu Chen of Zhao eventually sent General Han Guang to conquer Yan for Zhao, but upon his conquest, Han Guang appointed himself King of Yan. Han Guang had sent General Zang Tu to assist Xiang Yu, the king of Chu, in his war against Qin. When Zang Tu returned, Han Guang was ordered to become King of Liaodong instead. When Han Guang refused, Zang Tu killed him and declared himself King of both Yan and Liaodong.

Zang Tu submitted Yan to the Han dynasty during the war between Han and Chu in order to keep his title, but once the war was finished he revolted. Liu Bang (later Emperor Gaozu of Han) sent Fan Kuai and Zhou Bo to put down the rebellion, and they captured and executed Zang Tu. His son Zang Yan fled to exile among the Xiongnu.

Lu Wan became the new King of Yan and reigned there for most of Liu Bang's life, until the emperor discovered that he had sent officials to the courts of the rebel Chen Xi and the Xiongnu chanyu Modu. Summoned to the imperial court, Lu Wan feigned illness and then fled to the Xiongnu, who honored him as the King of the Eastern Nomads (Donghu) until his death. In the meantime, Yan came under direct control of the Han dynasty and was treated as a princely appanage.

Rulers

[edit]- Marquis Hui of Yan (燕惠侯)

- Marquis Li of Yan (燕釐侯)

- Marquis Qing of Yan (燕頃侯)

- Marquis Ai of Yan (燕哀侯)

- Marquis Zheng of Yan (燕鄭侯)

- Marquis Mu of Yan (燕穆侯)

- Marquis Xuan of Yan (燕宣侯)

- Marquis Huan of Yan (燕桓侯)

- Duke Zhuang of Yan (燕莊公)

- Duke Xiang of Yan (燕襄公)

- Duke Huan I of Yan (燕桓公)

- Duke Xuan of Yan (燕宣公)

- Duke Zhao of Yan (燕昭公)

- Duke Wu of Yan (燕武公)

- Duke Wen I of Yan (燕文公)

- Duke Yi of Yan (燕懿公)

- Duke Hui of Yan (燕惠公)

- Duke Dao of Yan (燕悼公)

- Duke Gong of Yan (燕共公)

- Duke Ping of Yan (燕平公)

- Duke Jian I of Yan (燕簡公)

- Duke Xiao of Yan (燕孝公)

- Duke Cheng of Yan (燕成公)

- Duke Min of Yan (燕閔公)

- Duke Jian II of Yan (燕簡公)

- Duke Huan II of Yan (燕桓公)

- Duke Wen II of Yan (燕文公)

- King Yi of Yan (燕易王)

- King Kuai of Yan (燕王噲)

- King Zhao of Yan (燕昭王)

- King Hui of Yan (燕惠王)

- King Wucheng of Yan (燕武成王) ruled 271–258 BCE

- King Xiao of Yan (燕孝王) ruled 257–255 BCE: son of King Wucheng

- King Xi of Yan (燕王喜) (姬喜 Ji Xi) ruled 255–222 BCE: last king of the Yan state

Rulers family tree

[edit]| Yan state | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Yan in astronomy

[edit]Yan is represented by the star Zeta Capricorni in the "Twelve States" asterism, part of the lunar mansion "Girl" in the "Black Tortoise" symbol.[10] Yan is also represented by the star Nu Ophiuchi in the "Left Wall" asterism in the "Heavenly Market" enclosure.[11]

Culture and society

[edit]Before the state of Qin unified China in 221 BC, each region had its own unique customs and culture, although all were dominated by an upper class that shared a largely common culture. In the Yu Gong (Tribute of Yu), a section of the Book of Documents which was most likely composed in the 4th century BC, the author describes a China that is divided into nine regions, each with its own distinctive culture and products. The core theme of this section is that these nine regions are unified into one state by the travels of the eponymous sage, Yu the Great and by sending each region's unique goods to the capital as tribute. Other texts also discussed these regional variations in culture and physical environments.[12]

One of these texts was The Book of Master Wu, written in response to a query by Marquis Wu of Wei on how to cope with the other states. Wu Qi, the author of the work, declared that the government and nature of the people were reflective of the terrain they live in. Of Yan, he said:

Yan's defensive formations are solid but lack flexibility(燕陳守而不走).[13]

and:

The Yan are a sincere and straightforward people. They act prudently, love courage and esteem righteousness while rarely employing deception. Thus they excel in defensive positions, but are immobile and inflexible. To defeat them, immediately apply pressure with small attacks and retreat rapidly. When they turn to face our attacks, we should keep a distance. Attack the rear as well where and when they least expect it. When they withdraw to face another threat, chase them. This will confuse their generals and create anxiety in their ranks. If we avoid conflict against their strong points and use our armored chariots to set ambushes, we can capture their generals and ensure victory.(燕性愨,其民慎,好勇義,寡詐謀,故守而不走。擊此之道,觸而迫之,凌而遠之,馳而後之,則上疑而下懼,謹我車騎必避之路,其將可虜)[13]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Wang Jijie (September 1, 2005). 燕国明刀分期研究及相关问题探讨 [Research on Yan Knife-Money and Related Topics]. Beijing Municipal Cultural Office (in Chinese). Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "The History of Yanshan". Yanshan Central Information Office (in Chinese). Beijing Municipal Government. October 18, 2008. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Chen Zhi (September 30, 2010). 從王國維. 学灯 (in Chinese) (16). Confucius 2000. Archived from the original on July 26, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Ji, the Capital of the State of Yan". Beijing Municipal Administration of Cultural Heritage. June 16, 2006. Archived from the original on July 7, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ "Site of the Second Capital of State of Yan". The People's Government of Hebei Province. China Daily. December 29, 2009. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ 蓟城纪念柱 [dead link]

- ^ "Liulihe Site". China Culture. Archived from the original on 2012-09-25.

- ^ Juliano, Annette L (1991). "The Warring States Period—The State of Qin, Yan, Chu, and Pazyryk: A Historical Footnote". Notes in the History of Art. 10 (4): 25–29. doi:10.1086/sou.10.4.23203292. JSTOR 23203292. S2CID 191379388.

- ^ Mencius. (2008). Mengzi : with selections from traditional commentaries. Van Norden, Bryan W. (Bryan William). Indianapolis: Hackett Pub. Co. p. 56. ISBN 9780872209138. OCLC 181421046.

- ^ Chen Guanzhong; Chen Hui-Hwa (July 4, 2006). 中國古代的星象系統 (65): 女宿天區 [Ancient Chinese astrological system (65)]. Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy (AEEA) 天文教育資訊網 (in Chinese). Taiwan: National Museum of Natural Science. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Chen Hui-Hwa (June 23, 2006). 中國古代的星象系統 (54): 天市左垣、市樓 [Ancient Chinese astrological system (54)]. Activities of Exhibition and Education in Astronomy (AEEA) 天文教育資訊網 (in Chinese). Taiwan: National Museum of Natural Science. Retrieved July 26, 2011.

- ^ Lewis 2007, p. 11-13.

- ^ a b Wuzi,also known as Master Wu

Bibliography

[edit]- Lewis, Mark Edward (2007). The Early Chinese Empires: Qin and Han. London: Belknap Press. ISBN 978-0-674-02477-9.

External links

[edit]- Yan (state)

- History of Beijing

- Ancient Chinese states

- States of the Spring and Autumn period

- States of the Warring States period

- 11th-century BC establishments in China

- States and territories established in the 11th century BC

- States and territories disestablished in the 3rd century BC

- 3rd-century BC disestablishments

- 1st-millennium BC disestablishments in China