Minden

Minden | |

|---|---|

Old Town Hall of Minden | |

Location of Minden within Minden-Lübbecke district  | |

| Coordinates: 52°17′18″N 08°55′00″E / 52.28833°N 8.91667°E | |

| Country | Germany |

| State | North Rhine-Westphalia |

| Admin. region | Detmold |

| District | Minden-Lübbecke |

| Founded | 798 |

| Subdivisions | 19 quarters |

| Government | |

| • Mayor (2020–25) | Michael Jäcke[1] (SPD) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 101.12 km2 (39.04 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 42 m (138 ft) |

| Population (2023-12-31)[2] | |

| • Total | 83,100 |

| • Density | 820/km2 (2,100/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+02:00 (CEST) |

| Postal codes | 32423, 32425, 32427, 32429 |

| Dialling codes | 0571, 05704, 05734 |

| Vehicle registration | MI |

| Website | www |

Minden (German: [ˈmɪndn] ) is a middle-sized town in the very north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, the largest town in population between Bielefeld and Hanover. It is the capital of the district (Kreis) of Minden-Lübbecke, which is part of the region of Detmold. The town extends along both sides of the River Weser, and is crossed by the Mittelland Canal, which is led over the river on the Minden Aqueduct.

In its 1,200-year written history, Minden had functions as diocesan town from 800 CE to the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 CE, as capital of the Prince-Bishopric of Minden as imperial territory since the 12th century, afterwards as capital of Prussia's Minden-Ravensberg until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806, and as capital of the East-Westphalian region from the Congress of Vienna until 1947. Furthermore, Minden has been of great military importance with fortifications from the 15th to the late 19th century, and is still a garrison town.

Minden hosts diverse industries, none predominant. The town has been terminus of one of the oldest German railway trunks since 1847, adding to the multimodal transport hub between its harbour, federal roads, and a nearby highway (Autobahn) junction.

Geography

[edit]Location

[edit]

Minden is a town in the northeastern part of the German federal state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The town is crossed by the Weser flowing north. The town centre lies on a plateau on the western side of the river 5 kilometres (3 miles) north of the Porta Westfalica gap between the ridges of the Weser Hills and Wiehen Hills, where the Weser leaves the Weser Uplands and flows into the North German Plain. The small Bastau stream flows into the Weser from the west near the town centre. The edge of the plateau marks the transition from the Middle Weser Valley to the Lübbecke Loessland, divides the upper town from the lower town, and marks the boundary between two ecological zones.

In the frame of Natural regions of Germany, the western part of Minden belongs to a sequence of geomorphological units (from south to north): the Wiehen Hills, the Lübbecke Loessland, therein the Bastau depression, and the Dümmer Geest Lowland. The eastern part lies in the Middle Weser Valley depression.

Crossing the Weser valley was once favoured by a ford with a break in the middle; there its meander touches the western edge of the valley, the eastern floodplain is usually flood-meadow, so that the central bridgehead (Brückenkopf) becomes a river island. Today a system of two bridges crosses the valley.

The Mittelland Canal connecting the river systems of Ems, Weser and Elbe traverses the town from west to east. These waterways cross in the northern area of the town at the Minden Aqueduct (Wasserstraßenkreuz Minden).

The Weser leaves the Minden area at its lowest part in the quarter of Leteln, at 40 metres (131 feet), while the highest part is the top of Häverstädter Berg with 272 metres (892 feet), at the edge of the Wiehen Hills in the quarter of Haddenhausen. The altitude of the town is given officially as 42.2 metres (138.5 feet), based on the elevation of the town hall.

The town covers an area of 101.12 square kilometres (39.04 sq mi). It extends 13.1 km (8.1 miles) from north to south and 14.1 km (9 mi) from east to west.

Minden is 40 kilometres (25 miles) northeast of Bielefeld, 60 km (37 miles) west of Hanover, 80 km (50 mi) south of Bremen and 60 km (37 mi) east of Osnabrück.

Neighbouring settlements

[edit]The neighbouring towns and communities of Minden are (clockwise from north): Petershagen, Bückeburg (Schaumburg District in Lower Saxony), Porta Westfalica, Bad Oeynhausen, and Hille.

Town subdivision

[edit]Minden is administratively divided into 19 quarters:

- Bärenkämpen

- Bölhorst

- Dankersen

- Dützen

- Haddenhausen

- Häverstädt

- Hahlen

- Innenstadt (town centre)

- Königstor

- Kutenhausen

- Leteln-Aminghausen

- Meißen

- Minderheide

- Nordstadt

- Päpinghausen

- Rechtes Weserufer

- Rodenbeck

- Stemmer

- Todtenhausen

The area of the historical town until the 19th century is today part of the quarter Innenstadt.

Climate

[edit]Minden has no meteorological station, therefore the data of the next station Bückeburg in distance of 10 kilometres (6 miles) are given.[3]

| Climate data for Bückeburg[a] (1991–2020 normals) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 4.6 (40.3) |

5.6 (42.1) |

9.3 (48.7) |

13.9 (57.0) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.2 (70.2) |

24.0 (75.2) |

23.7 (74.7) |

19.5 (67.1) |

13.8 (56.8) |

8.2 (46.8) |

4.7 (40.5) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.8 (37.0) |

3.1 (37.6) |

5.8 (42.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

18.7 (65.7) |

14.9 (58.8) |

10.4 (50.7) |

6.4 (43.5) |

3.5 (38.3) |

10.3 (50.5) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −0.1 (31.8) |

−0.1 (31.8) |

2.2 (36.0) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.9 (48.0) |

11.6 (52.9) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.0 (57.2) |

11.1 (52.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

3.4 (38.1) |

0.3 (32.5) |

6.5 (43.7) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 58.3 (2.30) |

45.2 (1.78) |

46.3 (1.82) |

40.6 (1.60) |

63.2 (2.49) |

59.0 (2.32) |

71.4 (2.81) |

76.1 (3.00) |

60.5 (2.38) |

59.7 (2.35) |

56.4 (2.22) |

56.1 (2.21) |

716.8 (28.22) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.1 mm) | 18.2 | 16.1 | 15.8 | 13.6 | 13.8 | 14.7 | 15.5 | 15.1 | 13.9 | 16.0 | 17.7 | 18.4 | 191.3 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 1.0 cm) | 4.1 | 4.7 | 1.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1.3 | 3.5 | 15.6 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 82.8 | 79.7 | 75.8 | 70.1 | 69.0 | 70.2 | 69.8 | 70.7 | 76.6 | 81.5 | 84.5 | 84.6 | 76.6 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 46.4 | 69.8 | 112.2 | 177.0 | 203.3 | 202.1 | 217.6 | 197.4 | 144.9 | 104.9 | 49.1 | 38.8 | 1,551.8 |

| Source: NOAA[4] | |||||||||||||

The meteorological data of the whole East-Westphalian region comply with zone Cfb of the Köppen climate classification, named as Temperate Oceanic climate. This rough classification gives no suitable and detailed description of the regional situation.[5] The furthest north-eastern part of East-Westphalia is the driest of the state,[6] though located in a small distance to the sea, caused by the main direction of the cyclones from roughly west to east with its prevailing south-westerly rain-bringing weather fronts. So the Minden region lies in the leeward rain shadow of the Teutoburg Forest and the Wiehen Hills. A cloudy weather south of the Wiehen Hills is often connected with clear sky in the north of the hills.[7]

Geology, mineral deposits and their use

[edit]

The Wiehen Hills escarpment extends more than 100 kilometres (62 mi) from west of Osnabrück to the Porta Westfalica gap and is continued in the Weser Hills range. The escarpment forming horizons incline gently flattening to the north; they are of jurassic age, overlayed by cretaceous sediments that form the hill of Bölhorst, and tertiary layers further to the north. The underground basis is of palaeozoic material from Devonian to Permian. A new[when?] described genus of dinosaur, the Wiehenvenator, was found in the Wiehen Hills near Haddenhausen, popularly referred to as the "Monster of Minden".[8]

The Porta sandstone (Portasandstein) of the Wiehen Hills has been used as building material for centuries and is seen in many public and private buildings in Minden and the region. Another valuable material is iron ore, that was being mined until the first half of the 20th century. Mining relics remain: e.g. the Potts Park, an amusement park in Dützen, on a former ore mine.[citation needed]

The Bölhorst hill 2 kilometres (1.2 mi) north of the Wiehen Hills is formed by horizons of Lower Cretaceous age and, in geological sense, is the western extension of the eastward Bückeberg in the Schaumburg district. In both elevations the hard coal containing Berriasian layers reach near to the surface. By reason of the correspondence of the Bückeberg Formation to the Wealden Group, the type of coal found here was named Wealdenkohle in German. Mining in the Minden Coalfield started in the 17th century during the Swedish occupation and ended in the late 19th century.[9] Another coal mine in the eastern quarter of Meißen worked from 1878 to 1958.[10]

A source of 10-percentage brine with its origin in the deep Zechstein series was pumped in the Bölhorst mine and once used for balneotherapy.[citation needed]

The last relief-forming age was the pleistocene. During the Saalian glaciation the whole region was ice-covered, now verified by glacial erratic rocks from Scandinavia placed for decoration in the town.[citation needed] The Bastau depression, a late-Saalian Weser bed, became a marshy peat-covered area; the peat is completely exhausted for its use in firing. In the time of Weichselian glaciation the glacier did not reach this region. In the periglacial climate of that time fine material (silt) was blown and accumulated north of the Wiehen Hills as well as north of the Bastau depression in either small west–east stripes of loess.

In the Weser depression, Weichselian gravel deposits are found and used in gravel pits.

Land use

[edit]

The forestry use of the considerably inclined Wiehen Hills shows a striking contrast to the nearly woodless loess stripes of the northern foothills as well as north of the Bastau depression. The loess developed to most fertile soils (luvisols) and has been used as arable land since prehistoric times. Both of its stripes are key traffic veins, today the Bundesstraße 65 from Minden to Lübbecke and the regional road from Minden to Espelkamp. The villages, so connected, have developed into settlements of considerable size.

The Bastau depression is wood and housing estate-free, having agricultural use. Only one north-south road passes through it, southwest of the town. The gleysols of this area as well as in the Weser valley depression are in agricultural use after drainage.

Four nature conservation areas extend completely or partly over Minden territory. The most northern of them provides a biological site (Biologische Station Nordholz) for education in ecology.

The percentage of woodland is smaller than in other towns of the same type.

| Settlement and traffic | Agriculture | Woodland | Other areas | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minden | 40.7% | 49.0% | 6.1% | 4.1% |

| Towns of same type in North Rhine-Westphalia |

31.9% | 42.7% | 22.4% | 3.0% |

History

[edit]Historical affiliations

Old Saxony bef.798–804

Duchy of Saxony 804–1180

Prince-Bishopric of Minden 1180–1648

Margraviate of Brandenburg 1648–1701

Kingdom of Prussia 1701–1807

Kingdom of Westphalia 1807–1810

First French Empire 1810–1813

Kingdom of Prussia 1813–1871

German Empire 1871–1918

Weimar Republic 1918–1933

Nazi Germany 1933–1945

Allied-occupied Germany 1945–1949

West Germany 1949–1990

Germany 1990–present

Ancient history

[edit]

The Minden area shows continuing settlement activity from the 1st to the 4th century, when it belonged to the Weser–Rhine Germanic development sphere. During the Roman campaigns in Germania, this part of Westphalia came into the focus of military activities. It remains a matter of discussion whether or not the Minden region was the location of the military camp from where commander Publius Quinctilius Varus began marching to the, for Rome disastrous, Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9 CE.[13] Likewise, the localization of the Battle of Idistaviso and the Battle of the Angrivarian Wall, both taking place in 16 CE, to the eastern part of Minden or its neighbour town of Porta Westfalica is uncertain.[14] Definite archaeological proofs for these locations have not been found as of 2024[update]. However, relicts of a temporary Roman military camp were found in Barkhausen in 2008, about 3.5 kilometres (2.2 mi) south of the centre of Minden.[15]

Middle Ages

[edit]

The name Minda was firstly mentioned in a Royal Frankish Annals record referring to an army assembly held by Charlemagne in 798 CE.[16] The location of the so-named settlement is supposed at the left river side, where today's Fischerstadt exists.[17] Directly neighbouring was the suspected site of a permanent frankish army camp and a royal estate, located favourably at the place where ways from the south were bundled by the Porta Westfalica gap, connected with a west–east way parallel to the Wiehen and Weser hills, and at a ford through the Weser. The region had already been converted to Christianity, when around 800 CE a bishopric was founded in Minden, one of the seven diocese foundations established under the rule of Charlemagne. The first cathedral was built nearby to the older village.[18] After the dissolution of the Duchy of Saxony in 1180 the bishop became sovereign of the Prince-Bishopric of Minden as a constitutional territory of the Holy Roman Empire, and remained in this status until 1648. During the Investiture controversy two bishops were nominated at the same time in 1080 both by the papal supporters and those of King Henry IV.

The Cathedral close on the lower Weser terrace was soon surrounded to the north and west by a settlement of artisans and merchants, who lived in a parish of their own. The development of the upper town began with the activities of ecclesiastical convents. A convent of Benedictine nuns removed from the Wiehen Hills to the northwestern edge of the town around St Mary approximately 1000 CE. In 1029, the Canonical Convent of St Martin appears, and a 1042-founded Benedictine monastery removed in 1434 from the Weser shore to a new upper site, where the monastery of St Mauritius was founded.[19] The Dominicane convent St Paul was established in 1236.

German medieval sovereigns governed their realms with an itinerant court, travelling from town to town. Louis the German hold an imperial assembly in Minden in 852. The Emperors of the Ottonian and Salian dynasty visited Minden several times.[20] When Henry IV came to visit in 1062, a dispute between members of his entourage and citizens caused a fire that destroyed the cathedral and parts of the town.[21] The imperial visit of Charles IV in October 1377 was the last one until the end of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806.[22]

In 1168, Henry the Lion, Duke of Saxony, married his second wife Matilda, daughter of Henry II of England, in Minden Cathedral; with this marriage Henry maintained the continuance of the House of Welf.[23]

The rights to hold a market, to mint coins, and to collect customs duties were granted in 977 by Emperor Otto II. Until the beginning of the 13th century, the bishop appointed the Wichgraf as secular administrator of the town. The citizens of Minden and their council obtained independence from the bishop's rule around 1230 and received a town charter in 1301. The increased self-confidence of the citizens was demonstrated by the construction of the town hall, probably adjoining the separately governed cathedral precinct.[24] As a result, the Bishop moved his official residence from Minden to Petershagen in 1307.

The economic development of Minden was influenced by its location on a navigable river and by its success in grain trading since the Middle Ages. Minden got the right to store goods and could force passing ships to unload their cargo; furthermore the town became a flourishing member of the Hanseatic League.[25] The precise year of the first Weser bridge construction is not known. A previous wooden pedestrian bridge was replaced in the late 13th century by another one fit for wagon transport. In the early 16th century Minden got a stone arch bridge.[26]

Modern era since the Reformation

[edit]

At the end of the medieval age the papal legate Cardinal Nicholas of Cusa visited some German church provinces to remedy deficits in pastoral care and clerical administration. During his journey he stayed in Minden for one week in August 1451, where he signed various decrees, but on the whole this project did not achieve the intended aims.[27] The Lutheran Reformation was introduced in 1529 during a vacancy after the death of the not very respected Bishop Francis of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, and a 36-man unit constituted itself as town regiment. A new church order, based on Martin Luther's principles, was announced from the pulpit of St Martin's Church (Martinikirche) on 13 February 1530. The Dominican convent was dissolved in 1529, and its buildings have been used since 1530 as a location of the new founded municipal Gymnasium, the first Protestant Gymnasium in Westphalia.

Imperial Catholic troops occupied Minden from 1625 to 1634 during the Thirty Years' War. Protestant Swedish troops laid siege to Minden and captured it in 1634. Queen Christina of Sweden (r. 1632–1654) granted Minden full sovereignty in internal and external affairs. During the Catholic occupation the bishop ordered the introduction of the Gregorian calendar in 1630; the calendar was re-set in 1634 under the Swedish régime, but finally standardized to the new style in 1668.[28]

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 secularized the Prince-Bishopric to the Principality of Minden and assigned the territory to the Prince Electorate of Brandenburg,[25] later named Brandenburg-Prussia. Swedish troops moved back in 1650, and the principality administration was restored from Petershagen to Minden in 1668. The Brandenburgian "Great Elector" Frederick William (r. 1640–1688) confirmed all traditional rights of the town,[29] but under his successors King Frederick I (r. 1688–1713) and Frederick William I (r. 1713–1740) the town was subordinated to the strongly centralized Prussian government in the spirit of absolutism. The 400-year civil self-determination ended with two town regulations from 1711 and 1721; the representatives of the town were no longer elected for a certain period, but for life, and they needed royal confirmation for inauguration.[30]

The Battle of Minden took place some miles to the north of Minden on 1 August 1759, during the Seven Years' War of 1756 to 1763. The allied forces of Prussia, Great Britain, and some German allies defeated the allied French and Saxonian troops in a decisive battle. The region remained Prussian, with the adjacent region in the possession of the British King George II (being the Prince-elector of Hanover in personal union). Because French troops had occupied the town twice during the war, King Frederick the Great realized that it could no more be defended in the old manner; thus he gave order to annul Minden's status as a fortress in 1764.[31]

The town functioned as the capital of the Prussian territory of Minden-Ravensberg from 1719 to 1807 and as the seat of the upper administrative authority named Kriegs- und Domänenkammer (Chamber of War Affairs and State Property), that ruled Minden-Ravensberg together with the Prussian territories of the County of Lingen and the County of Tecklenburg. The most prominent president of the chamber was the Baron vom Stein (in office from 1796 to 1803).

The Weser had long been an important trade route, and the legal regulation of trading had immense significance. In 1552 Emperor Charles V conferred the privilege of its merchants' unhindered trading on the whole Weser to the town of Minden. During the Thirty Years' War, Emperor Ferdinand II confirmed the staple right to Minden in 1627, meaning that all passing merchants had to offer their goods for sale for some days. As other towns on the Weser – like Bremen and Münden – had similar rights, many conflicts arose about the partly contradictory legal positions.[32][33]

From the Napoleonic Wars to World War I

[edit]

In course of the War of the Fourth Coalition, French troops occupied the town on 13 November 1806. In the following year Napoleon founded the Kingdom of Westphalia, governed by his brother Jerome Bonaparte as king, and Minden became part of this client state until 1810 as district capital in the Weser department. On 1 January 1811 Napoleon moved Minden to the department Ems-Supérieur of the French Empire; now the Weser formed the eastern frontier between France and Westphalia. The rights of the Cathedral chapter in the cathedral close were abolished, the still existing convents were dissolved, and some ecclesiastical buildings like St John's church were secularized and used for military purposes. Before the French troops abandoned Minden on 3 November 1813 after the disastrous Battle of Leipzig, they blew up some of the arches of the Weser bridge, with the damage replaced for decades by a wooden auxiliary construction only.[34]

Minden became part of the Kingdom of Prussia again as capital both of the District of Minden and the government region (Regierungsbezirk Minden) in the new formed Province of Westphalia. By royal order it was declared a fortress once more. The fortress regulations ordered a 600-metre (2,000 ft) area in front of the wall being free of any buildings, not even vertical gravestones were allowed.[35] The refortification had severe consequences, hindering any extension of the town area and thus economic development. The Infanterie-Regiment "Prinz Friedrich der Niederlande" (2. Westfälisches) Nr. 15 was stationed in the garrison from 1820 to 1919, when it was dissolved; the naming Colonel-in-chief was Prince Frederick of the Netherlands and after his death Queen Emma of the Netherlands. Frederick's wife Princess Louise of Prussia was Colonel-in-chief of the Infanterie-Regiment "Graf Bülow von Dennewitz" (6. Westfälisches) Nr. 55, that was partly stationed in Minden, too. Since 1999, the Feldartillerie-Regiment Nr. 58 encamped a new barracks area in the nordwest of the town centre. The Hanoveran Pionier-Battalion No. 10 was part of the X Corps, that was incorporated into the Prussian Army after the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, and had its barracks near to Minden station. The main military training area was a large location in today's quarter of Minderheide at the very northwest edge of the town, an area that had already been part of the main fighting during the Battle of Minden in 1759.[36]

After the Congress of Vienna of 1815 had passed general principles of free traffic on the main rivers, the six Weser-states of the German Confederation annulated all restrictions and most of the financial burdens for shipping on the river by the Weser Shipping Act (Weserschifffahrtsakte) of 1823.[37] The first steam ship was put in operation in 1836, and a first harbour basin was built in 1859 on the east side of the river, connected with the railway in 1863. In the following decades, the great majority of transferred goods were imported goods, as export was of low importance. Inland shipment grew enormously after the completion of the Mittelland Canal and its connection to the Weser by the shaft lock in 1915.[32]

The trunk line of the Cologne-Minden Railway Company was opened in 1847 with a solidly fortified station and connected with the Hanover–Minden railway.[38] After defortification,[further explanation needed] the railway got an important momentum for economic growth in Minden.

The spatial narrowness in the fortress restricted the development of industrial firms of different branches to a certain degree, but did not prevent it.[39] The dominant industry, as well as in the whole district, was the manufacture of cigars; this branch decreased after World War I and finally vanished, because the growing market share of cigarettes had been ignored. Minden was seat of a Chamber of commerce from 1849 to 1932, when it was merged with those of Bielefeld.[40]

Overpopulation and unemployment were the reasons for an enormous emigration from the Minden Land; various emigration agencies had their location in Minden.[41]

The town remained a Prussian fortress until 1873, when Germany's Imperial Diet (Reichstag) passed the law to remove the fortress status of several fortified places, among them Minden. The fortress walls were razed by 1880 – the town had to pay for it – and a new Weser bridge was constructed, permitting the town to catch up economically. However, it was never able to regain its former political and economic importance.[42]

The upper class used the new conditions for construction of a new town quarter in a half-circle to the north and west of the old centre with prestigious buildings on spacious plots, but the urgent narrowness inside the centre maintained.[43] A lot of buildings in the style of historicism replaced older ones at the market place and in the main streets.[44] The lack of buildings outside the fortifications was favourable for planning a road network in the outer areas of the town. Since the 1890s, a sequence of six ring roads in the west and north of the town has formed the backbone of the road network.[45]

Grandiose festivities took place when Emperor William II and Empress Auguste Victoria visited Minden and the southern village of Barkhausen for inauguration of the Emperor William Monument on the Wittekindsberg above the Porta Westfalica gap on 18 October 1896. Since then the monument has been a visible element of the southern view from Minden.[46] The first line of the Minden tramway has connected the primary site of the memorial with Minden since 1893 when the memorial was still under construction.[47]

The Minden District Railways (Mindener Kreisbahnen), founded in 1898, built up a narrow-gauge railway net with three lines until World War I.[48] Minden got a municipal water supply system in the 1880s[49] and an electric power station in 1902.[50]

The Weimar Republic and the Nazi Regime

[edit]

The republican November Revolution of 1918 passed with only small disturbances that occurred in a few barracks of the Minden garrison on 7 and 8 November 1918. A workers' and soldiers' council, most of them members or supporters of the Social Democratic Party, took control in the afternoon of 18 November, but co-operated both with the town council and the military and civil administration as well and was successful in calming the situation.[51]

The situation became more critical during the Kapp Putsch of March 1920, when right-wing officers tried to overthrow the legitimate government of the German Reich. A majority of the town council declared their loyalty to President Friedrich Ebert and Chancellor Gustav Bauer, who for their part confirmed the authority of the Minden Workers' Council. The assassination of Foreign Minister Walther Rathenau on 24 June 1922 resulted in serious rioting in Minden. A demonstration of 15,000 people in support of the government was held at the market square on 27 June. Public opinion changed during the time of the Great Depression, and in the 1930-election of the town council, the NSDAP received 6 of 31 seats, and in the 1933-election, the last democratic one, they won a majority comprising 16 of 28 seats.[52] The NSDAP increased their Minden results of the Reichstag elections from 2.0 percent in May 1928 to 40.1 percent in July 1932.[53]

Although the German armed forces were restricted considerably by the regulations of the Treaty of Versailles, Minden remained a garrison town of the Reichswehr with the Pioneer Battalion No. 6 and the Artillery Regiment No. 6, both parts of the 6th Division. However, soldiers became more and more connected with right-wing groups, although officially obliged to political neutrality. The military units put forward the construction of sporting facilities: a stadium (Adolf-Hitler-Kampfbahn, now Weserstadion), a public open-air pool (now Sommerbad), and a horse racecourse. Both Walther von Brauchitsch (who organized annual horse tournaments from 1925 to 1927) and Wilhelm Keitel (who succeeded him in the same function until 1929) spent part of their career in Minden.[54]

When the Reichswehr was transformed to the Wehrmacht in 1935, army units were enlarged. Minden received another pioneer battalion (No. 46), new barracks (Mudra-Kaserne, after WWII Clifton barracks) and an exercise area at the Weser shore were built. After the last prisoners of war had left the camp area Minderheide in 1922, the place was used again for military exercise, horse and motorcycle sport, and a part from it as a place to land for small planes, as had already been happened starting in 1910. Two hangars and workshops for repairing and overhauling were built in this area beginning in 1936, where new types of planes were also tested.[55]

After the war, the Minden District railway opened a fourth line to the coal mine of Meißen and the ore mine of Kleinenbremen, and in 1924 began to convert the narrow gauge to standard gauge tracks.[56] The Minden tram was electrified in 1920, and three lines were added by 1930.[47]

In 1929, the Melitta firm transferred its production from Dresden to Minden. From 1935 the Chemische Werke Minden produced chemicals for pharmaceutical use, e.g. codeine; because of potentially military interest the producing company Knoll AG in Ludwigshafen had decided for a more inner-German producing location.[citation needed]

From 1934 to 1940, two suburbs with single-family houses of modest size (Siedlung Kuhlenkamp and Siedlung Rodenbeck) were created in considerable distance to the previous settlements.[57] Like in other communities, the names of some streets or places were changed for political reasons during the Third Reich, with most being reverted in 1945.[58]

World War II

[edit]

During World War II, underground factories were built in the Weser Hills and Wiehen Hills near Minden. Slave labourers from a nearby subcamp of the Neuengamme concentration camp were forced to produce weapons and other war materiel. After the war the machinery was removed by American troops and the entrances were sealed.

Most of the Jewish citizens of Minden were deported, dispossessed and murdered. Stolpersteine (literally 'stumbling stones', metaphorically 'stumbling blocks') have begun to be laid within Minden's pavements as a memorial to them.[59]

Minden sustained severe damage from Allied bombings during World War II. These attacks were minor during the early phase of the war. The raid on 26 October 1944 on the canal aqueduct damaged the wall of the Mittelland Canal, and numerous workers in a nearby air raid shelter were drowned. The last and most devastating air raid was conducted by Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress aircraft of the United States Army Air Forces on 28 March 1945 and destroyed great parts of the town centre, including the town hall and cathedral, and resulted in the death of over 180 people.[60] At the end of the war 13% of all buildings were destroyed or damaged.[61]

When the Allied troops were approaching, the Nazi officials were ordered to leave the town to the east or the north; even the police and the firebrigade drew back, but Mayor Werner Holle remained. The 1st Canadian Airborne Battalion of the 3rd Parachute Brigade came from Bad Oeynhausen in the south, not through the Porta Westfalica gap but over the Wiehen Hills at the pass of Bergkirchen. On the evening of 4 April 1945 they took the town centre nearly without resistance. Almost all the bridges over the Weser and Mittelland Canal as well as the canal aqueduct had just been blown up by the German Army in a futile attempt to delay the Allied advance, according to Hitler's Nero Decree.[62][63] Before the retreat the army set fire to the Granary and the Army bakery; the spreading out of fire to the St Martin's church could be avoided only with great difficulties for lack of the fire brigade. In the first days of occupation a lot of plunder took place in the now police-less town.[64]

Postwar time

[edit]

In the early post-war time the Minden region became an important part of the British Occupation Zone. The British Military Government took its main location in Bad Oeynhausen before it moved to Berlin. The headquarter of the British Forces remained there until 1954. All the German Wehrmacht barracks in Minden were taken over by the British Army, as well as the former exercise area on Minderheide, where the St George's barracks were built in the following years, and on a nearby location the Kingsley barracks.[65] 466 houses were confiscated in 1945. As immediate measure, the British Army set up an auxiliary bridge (the Francis bridge), that was in use until the regular bridge was restored in 1947.[61]

The Economic Council for the British Occupation Zone (Wirtschaftsrat für die britische Besatzungszone) was founded in Minden on 11 March 1946 for reactivation of the German economy and supervised the work of the Central Office for Economy (Zentralamt für Wirtschaft) at the same place. The Zentralamt under its head Viktor Agartz fought against the policy of industrial dismantling and tried to reorganize the economy with perspectives of planned economy.[66] After the partial conjunction of the American and British Occupation Zones in 1947 to the Bizone, the Bizonal Economic Council continued the activities of the Minden Wirtschaftsrat in Frankfurt in the American occupation zone, where with Ludwig Erhard the course was changed to a market economy.

The town administration resumed its work on 9 April 1945 on a provisional basis. Subsequent to the foundation of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia in 1946, the Free State of Lippe was adjoined to it in 1947. Consequently Minden lost its position as a regional capital to the former Lippian capital Detmold in 1947. In contrast to the other Allied Powers, the British changed the German community regulation for their occupation zone in the way of strict separation of powers. Beginning in 1946, the mayor was merely an honorary position as head of town and chairman of the town council, with a professional town director (Stadtdirektor) being chief of administration.[67] In North Rhine-Westphalia these regulations were in force until 1998.

Parts of the Federal Railways Central Offices Bundesbahn-Zentralämter were moved to Minden in 1950. In the course of West German rearmament, the Herzog-von-Braunschweig-Kaserne (Duke of Brunswick Barracks) was built for the new garrison of the Federal Forces (Bundeswehr) in 1959 in the western quarter of Rodenbeck and another barracks in the quarter of Minderheide.

The town centre reconstruction adapted largely to the pre-war situation, the previous road system remained, and the destroyed houses were rebuilt in a 1950s style. Even in the undestroyed areas, dilapidated buildings were replaced by new ones that deviated from the quarter's character by form and volume.[68] The renewal of the main shopping street Scharn was planned by Werner March.[69]

The serious lack of housing in the 1950s and 1960s, caused by bombing and the post-war migration of refugees, was addressed with new housing areas, especially in the west and north of the centre. Furthermore, some housing estates for British soldiers' families were developed.[70]

The Minden tramway reduced the lines and finally stopped running in 1959; a trolley bus line on the right side of the Weser ran from 1953 to 1965.[47]

From the local government reorganization to present day

[edit]

On 1 January 1973, the previously separate surrounding communities of Aminghausen, Bölhorst, Dankersen, Dützen, Haddenhausen, Hahlen, Häverstädt, Kutenhausen, Leteln, Meißen, Päpinghausen, Stemmer, Todtenhausen as well as parts of Barkhausen, Hartum and Holzhausen II were incorporated into the town of Minden. Thereby the area of Minden increased from 29 square kilometres (11.20 sq mi) to 101 square kilometres (39.00 sq mi) and the population number from about 54,000 to 84,000.[71] At the same time the former districts of Minden and Lübbecke were merged to the new district (Kreis) of Minden-Lübbecke, of which Minden became the capital. A new district administration building was constructed south of the town centre on the site of an old barracks; the former administrative building has since then used as a community archive.[citation needed]

In the 1960s, ongoing problems with the town centre became increasingly urgent, such as high population density, large percentage of low-income persons, houses in poor condition, outdated business premises, unsuitable for pedestrians, and severe shortage of parking lots. Therefore, an urban renewal was carried out in the 1970s, within the frame of the federal law for urban development promotion (Städtebauförderungsgesetz, 1971), and subsidized by public money. Dilapidated buildings were renovated or replaced by new structures, although the removal of timber-framed houses was later regretted. The height of buildings was restricted to four or five storeys. The main shopping areas were rearranged to a pedestrian zone. Public traffic was kept away from the inner part with a new central bus station nearby. Since then private traffic has been inhibited from passing through the centre, but houses can still be reached by a dead end system. Two large parking areas at the edge of the town centre, an underground car park and several multistorey car parks provide parking facilities. To keep away the regional traffic, two new Weser bridges and a new bypass road in the very east were built; the old bridge was replaced in 1978.[72]

The administration of the enlarged town required a new building. Architect Harald Deilmann planned this complex directly from the old town hall to the cathedral court in the style of structuralism. Since its completion in 1977 it has been a matter of public discussion, not only for the look of the façade, but also for blocking the scenic view of the cathedral from the arches of the old town hall.[73] In 2006 a controversial resolution by the town council proposed the demolition of the town hall extensions to make room for a new shopping mall. However, a 57% majority opposed this plan in a referendum. Today the whole town hall building complex is classified as historical monument, and as of 2022[update] extensive renovation has been in progress since 2019.[74]

The shoreline of the Weser was improved in 1976 by extending the promenade to the Fischerstadt (Fishermen's Town). The Glacis, a park-like open space in front of the old fortifications, which was important as a green belt, was altered and made more accessible. The old town wall fronting the Fischerstadt was restored to its former height. The opposite shore area (Kanzlers Weide) has been made accessible by a footbridge. This improves access to a large parking area and festival site.

When British troops had left Minden in 1994, their barracks areas became valuable sites for further town development ("conversion areas").

Place of prosecution and imprisonment

[edit]Minden was the location of criminal prosecution or imprisonment in a number of very different cases.

- After the reformation, Minden was a stronghold of witch-hunts in Germany. There were 128 prosecutions for witchcraft between 1603 and 1684. As in nearby regions, almost all those sentenced persons were women.[75][76]

- Clemens August Droste zu Vischering (1773–1845), Archbishop of Cologne, was brought to Minden, where he was taken under house arrest from November 1837 to April 1839; he never returned to Cologne. During the so-called Cologne confusions (Kölner Wirren), Droste zu Vischering got in trouble with the Prussian state on the question of interconfessional marriages and the independence of the Faculty of Catholic Theology at the University of Bonn.[77]

- The physician Abraham Jacobi was born in the nearby village of Hartum and educated at the gymnasium in Minden. Though being acquitted as defendant in the Cologne Communist Trial in 1852, he was afterwards imprisoned and condemned of lese-majesty by the district court of Minden. After his release he emigrated to the US, where he became an important pediater.

- During World War I, a large prisoner-of-war camp was established in the western quarter of Minderheide. In September 1914 the first French and British soldiers were brought there, but only at the end of the year baracks were built for about 3,300 prisoners. Over the years more than 25,000 prisoners lived there. The camp was a main camp (Stammlager) with several external labour camps (Arbeitslager). Apart from British and French soldiers (including auxiliary troops from the colonies) Italians, Russians, Serbians, Croats, Poles, and Armenians were captured. The camp was dissolved after the Armistice of 11 November 1918, but the total dismantling lasted until 1922. The name Franzosenfriedhof (Cemetery of the French) of the nearby cemetery derives from a war memorial for French soldiers and is misleading, as the buried French, British, and Italian soldiers were transferred to their home countries after war. However, the gravesites of others, such as Russian, Serbian and Armenian, remain to date. In September 1917, Apostolic Nuncio Eugenio Pacelli visited the camp.[78][79][80]

- Auschwitz concentration camp commander Rudolf Höss was brought to Minden after being captured by the British in Schleswig-Holstein. In Minden, he was examined in the so-called Camp Tomato, where he, for the first time, confessed the murders of millions of Jews in his camp and signed a protocol on 15 March 1946. On 31 May he was brought to Nuremberg, where he repeated the confession as witness in the Nuremberg trials.[81][82]

Demography

[edit]| Nationality | Population | Nationality | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2678 | 413 | ||

| 1630 | 404 | ||

| 1471 | 346 | ||

| 804 | 333 | ||

| 569 | 316 | ||

| 475 | 300 | ||

| 433 | 299 |

Population growth[84]

|

|

|

(The sudden increase of population number in 1973 results from the administrative adjointment of the surrounding villages to the Minden town area.)

In the region Ostwestfalen-Lippe, which is congruent to the administrative region of Detmold, Minden takes the fourth place by population after Bielefeld, Paderborn, and Gütersloh.

The earliest detailed information on population size dates to 1740. During Prussian governance, Minden as a regional capital and garrison showed a gentle population growth by officials and soldiers, and then, after defortification, by industrial workers from the surrounding region.

After World War II, Minden's population increased significantly due to migration of expelled persons and refugees, mainly from former eastern territories of Germany. Beginning in the 1960s, population growth was mainly due to guest workers from mediterranean countries, many of whom subsequently chose to settle permanently in Minden.

Migration to Germany of ethnic Germans from the Soviet Union and its succeeding countries began in the 1980s, and the district of Minden-Lübbecke was one of their preferred regions. Then in 1989–1990, German reunification enabled migration of people from eastern Germany. The most recent migration period is due mostly to asylum seeking refugees from the Near East and the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Religions

[edit]Christians

[edit]

Protestant

[edit]The Reformation took hold in Minden between 1521 and 1529. The town contains six Protestant parishes today: St Mary's, St Martin's, St Mark's, St James' and the parishes of St Peter's and St Simeon's Churches. They all are parts of the Church District (Kirchenkreis) of Minden and belong to the Evangelical Church of Westphalia.[85]

Roman Catholic

[edit]According to the regulations of the Peace of Westphalia, Minden Cathedral remained in Catholic possession. During the population growth in the 19th century the small number of Catholics rose slowly, and because of the migration of expelled persons, working migrants, and refugees after World War II, the percentage of Catholics increased considerably among the population of Minden.

There are four Roman Catholic parishes in Minden: the parish of the cathedral St Peter and Gorgonius, and parishes of St Mauritius, St Paul and St Ansgar, which are all bound together to the Pastoral Cooperation (Pastoralverbund) Mindener Land as part of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Paderborn.[86]

Other Christian Communities

[edit]Christian communities include the New Apostolics, the Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses and others. Many of the Germans migrating from Russia and Central Asian countries belong to baptistic or mennonitic communities.

A small Quakers' community existed during the 19th century, but only their cemetery remains.[87]

Non-Christian Religions

[edit]

Jewish

[edit]A Jewish community has existed in Minden since 1270 and grew to around 400 members in the 19th century. After World War II the Jewish community was reconstituted and in 2020 had about 85 members. The Minden synagogue built in 1865 was destroyed in the November pogrom on 9 November 1938, so a new synagogue was inaugurated nearby in 1958.[88][89]

Muslims

[edit]In the last half century a considerable Muslim community has grown in Minden with three mosques.

Politics

[edit]Mayor

[edit]The mayor, elected every five years, is the head of the town, the leader of town administration and chairman of the city council. As of 2024[update], the mayor of Minden has been Michael Jäcke of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) since 2015, re-elected in 2020 with 54.3% of votes.

City council

[edit]

The Minden city council governs the city together with the mayor. Municipal elections are held every five years, most recently on 13 September 2020. Apart from the nationwide parties, the members of Minden council also belong to three local associations of independent voters.

| Party | Votes | % | +/- | Seats | +/- | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Democratic Party (SPD) | 10,856 | 36.38 | 21 | |||

| Christian Democratic Union (CDU) | 8,164 | 27.36 | 15 | |||

| Alliance 90/The Greens (Grüne) | 4,636 | 15.54 | 9 | |||

| Free Democratic Party (FDP) | 1,037 | 3.74 | 2 | ±0 | ||

| The Left (Die Linke) | 951 | 3.19 | 2 | |||

| Alternative for Germany (AfD) | 1,714 | 5.74 | 3 | ±0 | ||

| Mindener Initiative (MI) | 1,062 | 3.56 | 2 | |||

| BürgerBündnis Minden (BBM) | 735 | 2.46 | 1 | ±0 | ||

| Wir für Minden | 584 | 1.96 | New | 1 | New | |

| Total | 100.0 | 56 | ||||

| Electorate/voter turnout | 47.14 | |||||

| Source: State Returning Officer Kommunalwahlen 2020 | ||||||

Elections to parliaments

[edit]The constituencies for state parliament (Landtag) and federal parliament (Bundestag) elections Minden belongs to, have been mostly won by candidates of the SPD.

Coat of arms, flag, motto

[edit]The coat of arms shows the doubled-headed imperial eagle (Reichsadler) of the Holy Roman Empire on the right, awarded in 1627 by emperor Ferdinand II for support of the town in the Thirty Years' War. The left side shows the crossed keys of Saint Peter, patron of Minden cathedral, as part of the Prince-Bishop's coat of arms.

The red-white flag shows the colours of the Hanseatic league. The town's motto is Ius et aequitas civitatum vincula (Law and justice are the towns' ties).

Culture and sights

[edit]

Theatre and cabaret revues

[edit]

The neo-Baroque municipal theater (Stadttheater Minden) from 1908 has no ensemble, but is performance location for guest ensembles and regular symphony concerts of the North West German Philharmonic Orchestra (Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie). Since 2002 a project (Der Ring in Minden) has been running to perform all the operas of Richard Wagner.

Further theatre and cultural events occur with private sponsorship and are held in such locations as the civic centre Bürgerzentrum and the Theater am Weingarten. There are also theatre groups without fixed performance venues.

Minden is seat of the European Association of authors Die Kogge.[90]

Minden is the original location of the nationally known amateur cabaret Mindener Stichlinge; its foundation in 1966 makes it the oldest active cabaret in Germany. The town awards the prize Kabarett-Förderpreis Mindener Stichling every two years to support literary-political cabarets; the €4,000-prize is sponsored by the Melitta company as well as the local savings bank.[91]

Museums

[edit]Minden has a municipal archive and two significant museums. The Prussia Museum (Preußenmuseum Minden) is one of two museums of Prussian history in North Rhine-Westphalia. It is quartered in old barracks on Simeonsplatz (Simeon Square).[92] The second is the Minden Museum of History, Cultural Studies and Folklore (Mindener Museum für Geschichte, Landes- und Volkskunde), housed in a Weser Renaissance style row of patrician houses (Museumszeile).[93] The attached Coffee Museum (Kaffee-Museum) focuses on the 100-year-old coffee producer, Melitta.

Minden in seat of a mill association that takes care of over 40 historical mills in the surrounding district (wind-, water-, and horse mills), which have been restored as technical monuments; on Minden area two windmills are in Meißen and Dützen, and a reconstructed ship mill at the Weser shore.[94]

The Minden Museum Railway operates with old Prussian rolling stock on the Minden District Railway tracks.

Buildings

[edit]

Minden Cathedral originally dates to the 11th century, the westwerk with its entrance façade built in Romanesque style, while the early Gothic nave and aisles date from the 13th Century. Most of the old buildings around the cathedral were severely destroyed by bombing during the Second World War. The cathedral was reconstructed by architect Werner March by 1957. The nearby town hall with its picturesque 13th century arcade is a complete postwar construction in its upper floors.

The market square is surrounded by buildings in the 19th century style of historicism. The façade of house Flamme/Schmieding obtained a twice daily clock display in 2010. It features the popular origin myth of last independent Saxon leader Duke Widukind shaking hands with Charlemagne.[95][96]

The main pedestrian zone in the commercial centre of Minden extends from the market place to the north (Scharn) and then turning rectangular in the Bakers' street (Bäckerstraße) eastward to the Weser. The present buildings mostly date from the late 19th century, but some show reconstructed façades in the Weser Renaissance manner. North of the Bakers' street are some 17th to 18th century half-timber framing buildings and the secularized St John's church, now being the event location Bürgerzentrum (BÜZ). The pedestrian zone continues the market place to the south as Obermarktstraße (Upper market street) and leads to the upper town centre. Its skyline is dominated from the three churches of (from south to north) St Simeon, St Martin and St Mary, the tower of the latter being an eye-catcher over a long distance. In the southwestern part of the town centre many 16th to 18th century residential buildings have remained intact.

The upper town is accessible via a short path from the market place by the St Martin's steps (Martinitreppe) to the St Martin's churchyard (Martinikirchhof), today a parking area surrounded by the St Martin's church, the Old Mint (Alte Münze), the oldest secular stone building of Minden and one of the oldest in Westphalia, the Schwedenschänke (Swedish tavern bemoaning the Swedish occupation during the Thirty Years’ War), the renewed synagogue, and the Granary (Proviant-Magazin, now used as Weser-Kolleg school) and adjacent Army Bakery (Heeresbäckerei, now used as St Martin's parish centre) as military buildings of the 19th century. The last two buildings belong to the so-called Schinkel buildings (Schinkelbauten), as well as some buildings round the Simeon square south of the centre, for their style showing great resemblance to the manner of the famous Prussian architect Karl Friedrich Schinkel. One of the smallest buildings in Minden is the Windloch (wind hole) near St Martin's.

Some great public buildings have been placed in the glacis area from 1880 to the very modern times: the schools Ratsgymnasium, Kurt-Tucholsky-Gesamtschule, Herder-Gymnasium, Domschule, the Centre of justice, and the former Regional Government's building (Neue Regierung) and the neighboured old district administration building (now the local archive) both in neo-renaissance style; the new district administration building from 1977 follows to the south.

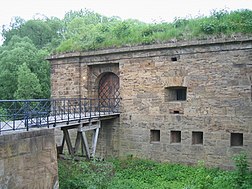

Because of its location near to the frontier between the Kingdoms of Prussia and Hanover, the railway station was strongly fortified from the beginning in 1847. Still extant are relicts of the station fortification with three forts. The station building itself is classified as an historical monument.

The picturesque Fischerstadt (fishermens' town) lies northeast of the town centre along the Weser, where remnants of the old town fortification wall are reconstructed. In the old villages now being town quarters a lot of half-timbered houses have remained. Schloss Hadenhausen (Haddenhausen Palace) is a 17th-century Weser Renaissance style manor house, still owned by the Bussche family, on the outskirts of the town.

The Kampa-Halle from the 1970s is a large gym-complex for sports and other events.

Monuments and public art

[edit]

Minden contains several monuments harking back to Prussian history. The monument of the Great Elector, the only one for a sovereign in Minden, stands alongside the Weser bridgehead to commemorate its first Prussian ruler. In the glacis area, monuments are placed for the infantry brigade and the artillery regiment stationed in Minden, for the World War I deads of the pioneer battalion, and the deads of both World Wars. Another memorial is topped by a bust of Friedrich Ludwig Jahn (1778–1852), the "father of gymnastics", and reminds especially at the dead gymnasts of Minden. The monument to the Battle of Minden is in the Todtenhausen quarter of the town; it commemorates the decisive victory of the forces of Great Britain and their German allies. On the Great cathedral court an obelisk-like monument, topped by the Prussian eagle, reminds at the Prussian victories in the Second Schleswig War of 1864 and the Austro-Prussian War of 1866, and a sarcophagus-like memorial in the glacis, designed by Karl Friedrich Schinkel, at Major General Ernst Michael von Schwichow (1759–1823), fortress commander of Minden.

The Weserspucker (Weser spitter) in the pedestrian zone symbolizes the connection with the river; he is spitting in intervalls. A memorial in pyramidion-form at the Mittelland Canal reminds of Leo Sympher (1854–1922), the leading hydraulic engineer of the canal construction, and a bust at the Martinitreppe of the Minden born astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel.

The new steel sculpture named Keilstück (Wedge piece) by artist Wilfried Hagebölling, that decorates the Martinikirchhof since 1987, has been disputed controversially in public opinion. In the early 2000s the town council decided to remove the sculpture, but caused thereby legal proceedings with the artist; finally the court of appeal confirmed the location at the original place.[97] In January 2022 the sculpture Pegelschlange (gauge snake) is placed in the flooding area at the Weser shore.[98]

-

The Great Elector by Wilhelm Haverkamp

-

Memorial to the Battle of Minden in Todtenhausen

-

Memorial for fortress commander Schwichow by Schinkel

-

War memorial (Großer Domhof)

-

Memorial to the Infantry Regiments

-

Memorial to the Artillery Regiments by Eberhard Encke

-

Memorial to the deads of the Artillery Regiment No. 58

-

Memorial for the deads of the Pioneer Battalions

-

Memorial for war-killed Minden gymnasts

-

Leo Sympher memorial at the Mittelland Canal

-

Keilstück on the Martinikirchhof in front of "Army bakery" (left) and "Granary"

-

The Weser spitter

-

Bust of astronomer Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel

Parks

[edit]The town centre is surrounded by the Glacis, a parklike green belt replacing the fortifications after their demolition. In its western part the glacis widens to a botanical garden with old tree specimens and thematic gardens on the site of the old cemetery, that was established in 1807, after burials on the old churchyards inside the town had been forbidden. In 1904 a new great cemetery was laid out in the north of the centre, and in 1957 another one in the south.[99]

Sport

[edit]

About 25.000 people are members of more than a hundred sport clubs, which are organized in a municipal sport association (Stadtsportverband), covering a great variety of disciplines.[100] The most successful club, the handball club GWD Minden, has played in the Handball-Bundesliga (national handball league) with some interruptions since the league's founding in 1966. GWD now plays in the "Kampa-Halle".

Minden has a reputation as a water sports centre with swimming, kanoe and kayak sport, and rowing, aided by its location on the Weser and the Canal. Many organizations participate in the organization of the major water sport festival "Blaues Band der Weser" which is held every other year.[101]

Mindener Freischießen

[edit]

The Mindener Freischießen (Minden Free Shooting) is a unique public festival that takes place usually every two years. It is arranged by the military-like organized Mindener Bürgerbatallion (Minden Citizen Battalion) with the Stadtmajor (Town Major) on top. The battalion is divided into six companies, a squadron and a drummer corps, each of them headed by a captain.

In the Middle Ages the right of self-government corresponded with the duty of self-defence, and the citizen battalion was established for this purpose. Since 1682 the obligatory shooting exercises were arranged as a public festival, and as a reward the best shooter was exempted from taxation in the current year. The festival's name refers to this rule. In 1685 the Great Elector changed the rule, so that the winner got a reward of 50 Thaler. This rule has remained to present days: now the Minister-President of North Rhine-Westphalia as legal successor of the Prince-Elector pays the honour sum in present currency; due to the biennial rhythm two winners are determined.

The festival usually takes place in June or July from Thursday to Sunday in the town centre. The Freischießen should not be confused with a marksmen's festival.

Other events

[edit]The Mindener Messe is a one-week travelling funfair every May and every November on the wide event-place Kanzlers Weide at the right Weser shore; it was founded in 1526 by the Prince-Bishop.

The Hahler Kranzreiten takes place every summer in the quarter of Hahlen. It is an equestrian competition where the contestants try to catch a gallows-hanging garland while riding on a galloping horse in several rounds; every following round the gallows is lifted to a higher position.[102]

Traditional Marksmen's festivals (Schützenfest) are arranged by marksmen's clubs (Schützenverein) in some quarters of Minden like in many other German cities.

Transport

[edit]Rail and bus

[edit]

Minden station is connecting point of the Hanover–Minden railway and the Hamm–Minden railway, which are part of the main lines connecting the Rhine-Ruhr region and Amsterdam with Berlin, and the secondary Weser-Aller Railway between Minden and Nienburg. The railway station is a stop for local and express trains such as Intercity-Express and InterCity.

Regional lines:

- RE 6 (Rhein-Weser-Express) Düsseldorf–Bielefeld–Minden,

- RE 60 (Ems-Leine-Express) / RE 70 (Weser-Leine-Express) Bielefeld/ Rheine–Minden–Hannover–Braunschweig

- RE 78 (Porta-Express) Bielefeld–Minden–Nienburg

Minden is terminal station of line S 1 of the Hanover S-Bahn to Hanover. All passenger platforms are accessible to handicapped persons.

The Minden District Railways (Mindener Kreisbahnen) run two freight lines, one from Minden to Hille (Mittelland Canal port) in the west and the other one to Kleinenbremen in the east. The Minden Museum Railway (Museumseisenbahn Minden) operates restored locomotives and rolling stock on these lines, in Kleinenbremen with the end at the visitors' mine.

The main station is connected by bus with the central bus terminal (Zentraler Omnibusbahnhof, ZOB) in the town centre, where 13 bus lines rendezvous every half-hour.[103] The local buses are coordinated with the regional buses to the other towns of the district.

Roads

[edit]The town lies close to the federal highways (Bundesautobahn) A 2 from Berlin to the Ruhr, and the A 30 to Amsterdam. The federal roads 61 and 65 cross in the town, the federal road 482 touches Minden as eastern ring road and connects the town with Nienburg and the next A 2-junction in Porta Westfalica. A dual carriageway connects the town to the south with Porta Wesfalica and Bad Oeynhausen. Two semicircle four-lane ring roads go around the town itself, the inner route 61 provides a town by-pass. The town centre has pay car parks and an automated guide to empty spaces.

Waterways and harbours

[edit]

The crossing of the navigable Weser and the Mittelland Canal is an important junction of the inland waterways system. Two locks (built 1914 and 2018) connect the River with the canal to overcome a difference in height of 13 m (43 ft).[104] The multimodal transport harbours on both Weser and Mittelland Canal are experiencing increasing volume because of the good waterway connections to the seaports of Bremen, Bremerhaven, and Hamburg. A new container port is in construction to the east of the present Mittellandkanal harbour, the so-called "RegioPort OWL", straddling Lower Saxony, being a seldom example of cross-State planning in the Federal Republic.

Minden hosts offices of the Waterways and Shipping Authority: Mittelland Canal / Elbe Lateral Canal (Wasserstraßen- und Schifffahrtsamt Mitelllandkanal/ Elbe-Seitenkanal) for the maintenance and regulation of these waterways.[105] An information centre is by the Minden Aqueduct (Wasserstraßenkreuz Minden), where the canal system and the function of the locks are explained.

Weser bridges

[edit]

The Weser is bridged over by seven overpasses: three road bridges, a railroad bridge, a pedestrian bridge, and a double aqueduct for the canal, which can be used by pedestrians, too. The main town bridge connects the town centre with the eastern suburbs and the railway station. The two relief bridges from the 1970s, the Gustav Heinemann Bridge in the north and the Theodor Heuss Bridge in the south, are four-lane and lead traffic away from town centre. A railway bridge carries the Minden District Railways' tracks over the Weser toward the main station. The Glacis bridge is a pedestrian suspension bridge that provides access to Kanzlers Weide, a large parking area and event place east of the town centre.

The next nearby road bridges are 10 km (6 mi) south at Porta Wesfalica and 20 km (12 mi) north at Petershagen.

Bicycle

[edit]The town is touched by two long-distance cycling routes: the Weserradweg (Weser bicycle path) along the complete river from Hann. Münden to Cuxhaven,[106] and starting point and terminus as well of the Westphalian Mill Route, that connects 43 historic mills along a circular route. A bike freeway from Minden to Herford (Radschnellweg RS 3) is under construction.[107]

The railway station sports a bike station. The town belongs to a working cooperative of bicycle-friendly communities in North Rhine-Westphalia aiming for bikes to exceed 20% of traffic.[108]

Hiking

[edit]Minden lies on the Wittekindsweg (Wittekind's path), part of the E11 European long distance path from The Hague to Tallinn, and on the regional pilgrims' route Sigwardsweg, named in memory of Bishop Sigward (1120–1140).[109]

A planet walk from Simeon square along the western Weser shore to the north symbolizes the planetary distances in the Solar System; it was established in 1996, when Pluto was yet regarded as planet, and therefore has a length of 5.9 km (3.7 mi).[110]

Economy and infrastructure

[edit]Economy

[edit]For a long time, Minden's economic development was hindered by the constraints of the fortress. In 1873, the fortress was dissolved, allowing the city and its economy to expand beyond its borders. Today, the city is home of about 3,600 businesses.[111]

Agriculture still occupies 50% of the administrative bounds, which have little changed. This is slightly more than the state average and much more than in the densely populated areas of the state.[112]

The average income in Minden is slightly below the average of the Minden-Lübbecke district and the state of North Rhine-Westphalia.[113] Thus, Minden ranks 309th out of 396 municipalities in North Rhine-Westphalia in terms of purchasing power.[114]

Minden is the economic centre of the district and the bordering region of Lower Saxony. It is part of an agglomeration corridor that extends along the A 2 Autobahn from Minden through Herford, Bielefeld, Gütersloh and on to the Ruhr area. Traffic connections by railway, highway, federal routes, and waterways are favourable factors for growing industry and trade with about 3,300 firms and 40,000 employees in regular conditions (2020).[115] A multitude of economic branches include the chemical, metalworking, electronic, paper, ceramic, and woodworking spheres, located on industrial areas mainly in the west and east parts of the town.

According to the three-sector model, the Minden employees work in the primary sector (agriculture, forestry) at 0.1%, in the secondary sector (industrial production) at 27.6%, and in the tertiary sector (mainly service and administration) at 72.4%; these numbers are roughly in accordance to the average of the state of North Rhine-Westphalia. The number of about 28,000 daily commuters exceeds the 17,000 citizens of Minden, who work outside the town's limits.[115] The disposable income per capita amounts slowly below to the average of North Rhine-Westphalia.[116]

Like in other towns, some great retail areas have deloped apart from the centre in the outer parts of the town. A very special problem of Minden results from the local government reorganization of 1973, when most of the surrounding suburbs were adjointed to the town administratively. The southern suburbs of Barkhausen and Neesen however became parts of the new founded town of Porta Westfalica, that since then has developed a large trading estate ("Porta Markt") in the most northwestern part of its quarter Barkhausen, directly to the border of Minden. The now established shopping scene is situated extremely marginally in the Porta Westfalica area, but the distance to Minden town centre is only 3 km (1.9 mi); by the federal route 65 even parts of the western community of Hille and the eastern town of Bückeburg are in the 15-minute radius.[117]

Enterprises

[edit]Minden is location of several middle-sized companies without a dominating industrial branch. As it is typical for the East Westphalian economy,[118] most of the Minden firms are small or middle-sized and often yet in ownership of the founder's family. No Minden firm is listed in the German premium stock indices DAX and MDAX, neither in the small-company index SDAX or the TecDAX for technological companies. Most of the greater firms have the status of private limited legal entities (Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung) or partnerships (Kommanditgesellschaft).

Melitta with headquarters in Minden is well known by consumers for its coffee products. The Strothmann corn brandy of rye distilled liquor is produced here by the Wilhelm Strothmann destilleries that is now part of the Berentzen group.[119]

Siegfried PharmaChemikalien Minden (former Knoll AG and lateron part of the BASF, now subsidiary of Siegfried AG in Switzerland) produces pharmacy chemicals as ephedrine, coffein and theophylline.[120] Another notable firm is Follmann, which produces special dyes and adhesives.[121] Ornamin Kunststoffwerke is a designer and producer of innovative plastic utensils like tableware and "To Go"-vessels, located in Minden since 1955.[122]

The Harting Technology Group, an electronics company originally founded in 1945, built an administration centre near to a former Prussian barracks area in the Glacis belt; the main locations of production were moved since 1950 to the nearby towns of Espelkamp and Rahden.[123] WAGO Kontakttechnik has its main location in the north of the town centre and produces connector products for the electric and electronic industry. Schoppe und Faeser was a producer of electronics that has been taken over by the ABB Group. Rose & Krieger, a subsidiary of Phoenix Mecano, produces technical components. The over 100-year-old Altendorf GmbH firm produces machine tools including the world leading circular trim saws.

The German retail food corporation Edeka has a regional office and distribution centre (Edeka Minden-Hannover) in Minden. The office is responsible for a large zone from the North Sea to north-east Germany including local branches of its 100%-subsidiary, low-price supermarket NP-Markt, as some functions of retailer WEZ (25% ownership).

The DB Systemtechnik (German railway system technology) deals with the development of rail vehicles and railway system equipment.[124]

The regional savings bank Sparkasse Minden-Lübbecke has its main administration in Minden.[125]

Media

[edit]The only local daily newspaper is the Mindener Tageblatt. The WDR (West German Broadcast) studio in Bielefeld provides a regional public broadcast, supporting the region of East Westphalia-Lippe with both radio and television programs. The TV transmission has its regional antenna on the Jakobsberg near Minden. The private radio station Radio Westfalica is part of the Radio-NRW group and transmits a local program from Minden focused on the District Minden-Lübbecke.

Public services and establishments

[edit]

The administration offices of the district of Minden-Lübbecke are in the Kreishaus (district building) near to the water affairs section of Detmold, its town presence.

The Minden Holding, a company in hands of the towns of Minden and Hameln, manages the supply with gas, electricity, and water with its subsidiary firms Mindener Stadtwerke[126] and Mindener Wasser; the waste disposal is done by the Städtische Betriebe Minden (municipal enterprises).[127] The 864 bed hospital Johannes-Wesling-Klinikum is one of four sites of the "Mühlenkreiskliniken" hospital-complex serving the district of Minden-Lübbecke. The new hospital building was completed in 2008 and is located in the southern town-quarter of Minden-Häverstädt.[128]

Minden's Centre of Justice houses seven discrete Administrative courts for North Rhine-Westphalia with competence for the whole administrative region of Detmold,[129] the Labour court (Arbeitsgericht) for controversies in employee-employer relationship in the district Minden-Lübbecke,[130] and one of the three Local courts (Amtsgericht) for criminal and civil cases in the district of Minden-Lübbecke.[131]

Minden is base of a German-British pioneer battalion (Deutsch/Britisches Pionierbrückenbataillon 130) in the Herzog-von-Braunschweig-Kaserne (Duke of Brunswick barracks) at the western town frontier.

Education

[edit]

The town provides all types of general-educating school. At present time (2024) there are eleven elementary schools (age 6 to 10),[132] four secondary schools (age 10 to 16), and five secondary schools with upper-level education (age 10 to 19, ending with the university entrance exam (Abitur),[133] two of them as comprehensive schools and the other three of type "gymnasium", a Freie Waldorfschule (age 6 to 18) and furthermore two vocational colleges.[134] The Weser-Kolleg offers adult people, already trained for practical occupation, a "second way of education" to get the Abitur, that provides access to university education.[135]

Minden has a branch of the Hochschule Bielefeld – University of Applied Sciences and Arts specializing in architecture, construction engineering, technology, engineering and mathematics, social studies, business and health at its Campus Minden, a former artillery barracks area of the Wehrmacht.[136] The Medizin Campus OWL is adjoint to the Johannes-Wesling-Klinikum as one of the study sites of the University Hospitals of the Ruhr-University of Bochum as a decentralized campus for medical students.[137] The RailCampus OWL, a cluster of some universities, enterprises and the German Railway for education and research in railway systems was built in 2022.[138]

Minden offers a Folk high school (Volkshochschule) serving also Hille, Petershagen, Porta Westfalica and Bad Oeynhausen,[139] and a municipal music school.[140]

Notable people

[edit]

- Master Bertram of Minden (c.1345–c.1415), painter

- Johann Vesling (1598–1649), physician

- Georg Wilhelm von dem Bussche-Haddenhausen (1726–1794), Hanoveran officer

- Caroline von Humboldt (1766–1829), art historian, wife of Wilhelm von Humboldt

- Ludwig von Vincke (1774–1844), Prussian statesman, Supreme President of Westphalia

- Friedrich Wilhelm Bessel (1784–1846), astronomer and mathematician

- Karl von Vincke (1800–1869), politician and officer

- Pauline von Mallinckrodt (1817–1881), founder of the order Sisters of Christian Charity

- Hermann von Mallinckrodt (1821–1874), politician

- Otto von Diederichs (1843–1918), Admiral

- Otto von Emmich (1848–1915), General

- Franz Boas (1858–1942), American anthropologist

- Ludwig Borckenhagen (1859–1917), Admiral

- Otto Quante (1875–1947), painter

- Hans Koeppen (1876–1948), officer and racing driver

- Gertrud von le Fort (1876–1971), writer

- Carl Hoffmann (1885–1947), cinematographer

- Richard Reimann (1892–1970), General

- Karl-Siegmund Litzmann (1893–1945), Nazi officer

- Franz Brandt (1893–1954), officer

- Hans Cramer (1896–1968), General

- Rolf E. Vanloo (1899–1941 ff.), film producer

- Hermann Bartels (1900–1989), architect

- Paul Kelpe (1902–1985), painter

- Heinrich Trettner (1907–2006), General of the Wehrmacht, Inspector General of the Bundeswehr

- Karl Strauss (1912–2006), brewer in Milwaukee

- Heinz Körvers (1915–1942), handball player

- Hans Wollschläger (1935–2007), translator of James Joyce and Edgar Allan Poe

- Herbert Lübking (born 1941), handball player, field handball world champion

- Jutta Hering-Winckler (born 1948), patron of music

- Sabine Leutheusser-Schnarrenberger (born 1951), politician

- Burkhard Schwenker (born 1958), manager

- Lutz Hachmeister (born 1959), media historian, filmmaker, journalist

- Wolfgang Rathert (born 1960), musicologist

- Angelika Brandt (born 1961), marine biologist

- Yves Eigenrauch (born 1971), footballer

- René Müller (born 1974), footballer

- Martin Schmeding (born 1975), concert organist and academic teacher

- Jan-Martin Bröer (born 1982), rower

- Thilo Versick (born 1985), footballer

- Tim Danneberg (born 1986), footballer

- René Rast (born 1986), racing driver

- Jan-Christoph Borchardt (born 1989), open source interaction designer

Notable residents

[edit]

- Heinrich von Herford (c. 1300–1370), Dominican

- Friedrich Hoffmann (1660–1742), physician in Minden garrison, inventor of the Hoffmannstropfen (Compound spirit of ether)

- Wilhelm Friedrich Ernst Bach (1759–1845), composer and music director

- Melitta Bentz (1873–1950), inventor of the coffee filter

Honorary citizens

[edit]Honorary citizenship was awarded to fourteen people totally;[141] yet living are handball player Herbert Lübking (born 1941) and former mayor Heinz Röthemeier (born 1924). Other honorary citizens were:

- Ludwig von Vincke (1774–1844), Prussian statesman

- August Karl von Goeben (1816–1880), general

- Alfred Meyer (1891–1945), Nazi official

Twin towns – sister cities

[edit] Gladsaxe, Denmark (1968)

Gladsaxe, Denmark (1968) Sutton, England, United Kingdom (1968)

Sutton, England, United Kingdom (1968) Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf (Berlin), Germany (1968)

Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf (Berlin), Germany (1968) Gagny, France (1976)

Gagny, France (1976) Tangermünde, Germany (1990)

Tangermünde, Germany (1990) Grodno, Belarus (1991)

Grodno, Belarus (1991) Changzhou, China (2015)

Changzhou, China (2015)

Minden has friendship relations to Tavarnelle Val di Pesa (Italy) and Attard (Malta). Minden took on the patronage for the expelled former inhabitants of the Pomeranian town of Köslin (now Koszalin in Poland).[142]

Gallery

[edit]-

Tower of St Martin's

-

St Peter's church

-

Windloch (wind hole), Minden's smallest house

-

Bahnhofskaserne (barracks near main station)

-

Fort A

-

Fort C

-

Shaft lock (1915), left: new lock (2018)

-

Oberpost-direktion (regional post office administration), now: revenue service building

-

Schloss Haddenhausen in Weser Renaissance style

Notes

[edit]- ^ Bückeburg is located approximately 10 kilometres (6.2 mi) south-east of Minden.

References