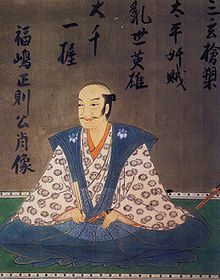

Fukushima Masanori

Fukushima Masanori | |

|---|---|

| 福島 正則 | |

Fukushima Masanori | |

| Lord of Hiroshima | |

| In office 1600–1619 | |

| Preceded by | Mōri Terumoto |

| Succeeded by | Asano Nagaakira |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ichimatsu 1561 Futatsudera, Kaitō, Owari Province |

| Died | August 26, 1624 (aged 62–63) |

| Nationality | Japanese |

| Spouse | Omasa |

| Parent |

|

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Unit | |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Miki Battle of Yamazaki Battle of Shizugatake Kyūshū campaign Korean campaign Battle of Gifu Castle Battle of Sekigahara |

Fukushima Masanori (福島 正則, 1561 – August 26, 1624) was a Japanese daimyō of the late Sengoku period to early Edo period and served as the lord of the Hiroshima Domain. A retainer of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, he fought in the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583 and soon became known as one of the Seven Spears of Shizugatake, alongside Katō Kiyomasa and others.

Biography

[edit]

Fukushima Ichimatsu, was born in 1561, in Futatsudera, Kaitō, Owari Province (present-day Ama, Aichi Prefecture), as the eldest son of the barrel merchant Fukushima Masanobu. However, some sources suggest that Masanobu may have been his father-in-law, with his actual father believed to be Hoshino Narimasa, a cooper from Kiyosu, Kasugai, Owari Province (present-day Kiyosu, Aichi Prefecture).[1] His mother was the younger sister of Toyotomi Hideyoshi's mother, making Hideyoshi his first cousin.[1]

As a young man, he served as a page (koshō) to Hideyoshi due to the familial connection through their mothers.[1]

He first saw battle during the assault on Miki Castle in Harima Province from 1578 to 1580. After the Battle of Yamazaki in 1582, he was awarded a stipend of 500 koku.

At the Battle of Shizugatake in 1583, he defeated Haigo Gozaemon, a prominent samurai.[2] Masanori (Tenshō 11) had the honor of taking the first head, that of the enemy general Ogasato Ieyoshi, and received a 5,000 koku increase in his stipend for this distinction (while the other six "Spears" each received 3,000 koku). He also married Omasa.

Masanori took part in many of Hideyoshi's campaigns. However, it was after the Kyūshū Expedition in 1587 that he was made a daimyō, receiving the fief of Imabari in Iyo Province with an income rated at 110,000 koku. Soon after, he participated in the Korean Campaign, where he gained further distinction by capturing Ch'ongju in 1592.[3] Following his involvement in the Korean campaign, Masanori was also involved in the pursuit of Toyotomi Hidetsugu.

In 1595, Masanori led 10,000 men, surrounded Seiganji Temple on Mount Kōya, and waited until Hidetsugu had committed suicide.[4] With Hidetsugu dead, Masanori received a 90,000 koku increase in his stipend and was granted Hidetsugu's former fief of Kiyosu in Owari Province.[5]

Conflict with Ishida Mitsunari

[edit]According to popular theory, in 1598, after the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, a conspiracy involving seven military generals—Fukushima Masanori, Katō Kiyomasa, Ikeda Terumasa, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Asano Yoshinaga, Katō Yoshiaki, and Kuroda Nagamasa—was planned to kill Ishida Mitsunari. The conspiracy was allegedly motivated by dissatisfaction with Mitsunari, who had written unfavorable assessments and underreported their achievements during the Imjin War against Korea and the Chinese Empire.[6]

Initially, these generals gathered at Kiyomasa's mansion in Osaka Castle before moving to Mitsunari's mansion. Mitsunari, however, learned of the plot through a report from Jiemon Kuwajima, a servant of Toyotomi Hideyori, and fled to Satake Yoshinobu's mansion with Shima Sakon and others to hide.[6] When the seven generals discovered Mitsunari was not at the mansion, they searched various feudal lords' residences in Osaka Castle and Kato's army approached the Satake residence. Consequently, Mitsunari and his party escaped from the Satake residence and barricaded themselves in Fushimi Castle.[7]

The next day, the seven generals surrounded Fushimi Castle, knowing Mitsunari was hiding there. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was responsible for political affairs at Fushimi Castle, attempted to mediate the situation. The seven generals requested Ieyasu hand over Mitsunari, which Ieyasu refused. Ieyasu then negotiated a resolution, agreeing to allow Mitsunari to retire and to review the assessment of the Battle of Ulsan Castle in Korea, which had been a major point of contention. Ieyasu's second son, Yūki Hideyasu, was assigned to escort Mitsunari to Sawayama Castle.[8]

However, historian Watanabe Daimon, based on primary and secondary sources, suggests that the incident was more of a legal conflict between the generals and Mitsunari rather than a conspiracy to murder him. Ieyasu's role was not to physically protect Mitsunari from harm but to mediate the complaints of the generals.[9]

Nevertheless, historians view this incident not merely as a personal conflict between the seven generals and Mitsunari but as an extension of the broader political rivalries between the Tokugawa faction and the anti-Tokugawa faction led by Mitsunari. Following this incident, military figures who were at odds with Mitsunari later supported Ieyasu during the Battle of Sekigahara, which pitted Tokugawa Ieyasu's Eastern Army against Ishida Mitsunari's Western Army.[6][10] Muramatsu Shunkichi, author of The Surprising Colors and Desires of the Heroes of Japanese History and Violent Women, assessed that Mitsunari's failure in his conflict with Ieyasu was largely due to his unpopularity among major political figures of the time.[11]

Campaign of Sekigahara

[edit]

On August 21, 1600, the Eastern Army alliance, which supported Tokugawa Ieyasu, attacked Takegahana Castle, defended by Oda Hidenobu, who sided with Mitsunari's faction.[12] The army was divided into two groups: 18,000 soldiers led by Ikeda Terumasa and Asano Yoshinaga moved towards the river crossing, while 16,000 soldiers led by Masanori, Ii Naomasa, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Kyogoku Kochi, Kuroda Nagamasa, Katō Yoshiaki, Tōdō Takatora, Tanaka Yoshimasa, and Honda Tadakatsu proceeded downstream to Ichinomiya.[13]

The first group, led by Terumasa, crossed the Kiso River and engaged in battle at Yoneno, causing Hidenobu's forces to rout. Meanwhile, Takegahana Castle was reinforced by a general from the Western Army faction, Sugiura Shigekatsu. On August 22, at 9:00 AM, the Eastern Army led by Naomasa and Fukushima crossed the river and launched a direct attack on Takegahana Castle. As a final act of defiance, Shigekatsu set the castle on fire and committed suicide.[12]

On September 29, Masanori, Ii Naomasa, and Honda Tadakatsu led their army to join Ikeda Terumasa's forces, where they engaged Oda Hidenobu's army in the Battle of Gifu Castle. This battle was part of the conflict between Oda Hidenobu of the Western Army faction led by Ishida Mitsunari. During the battle, Hidenobu's forces were deprived of expected support from Ishikawa Sadakiyo (石川貞清), who had decided not to assist the Western Army after reaching an agreement with Naomasa. Hidenobu was prepared to commit seppuku but was persuaded by Ikeda Terumasa and others to surrender to the Eastern forces, leading to the fall of Gifu Castle.[14][15]

On October 21, during the main Battle of Sekigahara, Masanori sided with Tokugawa Ieyasu's Eastern army. He led the Tokugawa advance guard and initiated the battle by charging north from the Eastern Army's left flank along the Fuji River, attacking the Western Army's right center. Masanori's troops engaged in what is considered one of the bloodiest confrontations of the battle against Ukita Hideie's army. Although Ukita's troops initially gained the upper hand, pushing back Masanori's forces, the tide turned when Kobayakawa Hideaki switched sides to support the Eastern Army. With this change, Masanori's forces began to gain the advantage, leading to an Eastern Army victory.

After Sekigahara, Masanori ensured the survival of his domain. Although he later lost his holdings, his descendants became hatamoto in the service of the Tokugawa shōgun.

Forfeit of titles

[edit]Shortly after Ieyasu's death in 1619, Masanori was accused of violating the Buke Shohatto by repairing a small part of Hiroshima Castle, which had been damaged by a flood caused by a typhoon, without proper authorization. Although Masanori had applied for permission two months prior, he had not received official approval from the bakufu. It is said that he repaired only the leaky part of the building out of necessity. The issue was initially resolved on the condition that Masanori, who was in Edo for his duties, would apologize and remove the repaired sections of the castle. However, the bakufu later accused him of insufficient removal of these repairs. As a result, his territories in Aki and Bingo Provinces, worth 500,000 koku, were confiscated, and he was instead granted Takaino Domain, one of four counties in Kawanakajima, Shinano Province and Uonuma County, Echigo Province worth 45,000 koku.

Nihongo spear

[edit]Nihongo spear (日本号), also known as Nippongo, is a famous spear that was once used in the Imperial Palace. It is one of The Three Great Spears of Japan. The Nihongo spear later came into the possession of Fukushima Masanori and then Tahei Mori. It is now housed at the Fukuoka City Museum, where it has been restored.

In popular culture

[edit]Fukushima Masanori is featured in Koei's video games Kessen, Kessen III, Samurai Warriors, as well as appearing as a non-playable character in Samurai Warriors 3. He is a playable character in the expansions for the third installment, Samurai Warriors 3 Z and Samurai Warriors 3: Xtreme Legends, as well as in the fourth installment, Samurai Warriors 4 and its subsequent expansions. Additionally, he is a playable character in Pokémon Conquest (known as Pokémon + Nobunaga's Ambition in Japan), with his partner Pokémon being Krokorok and Krookodile.[16]

He is mentioned in the movie Harakiri (1962). In the film, his fictional retainer, Tsugumo Hanshiro, is the protagonist.

Tachi

[edit]Fukushima Masanori's tachi is valued at 105 million dollars and is referred to as "the most expensive sword in the world." It is now held in the Tamoikin Art Fund.[17]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Fukushima masanori : Saigo no sengoku busho. Takeichiro Fukuo, Atsushi Fujimoto, 猛市郎 福尾, 篤 藤本. 中央公論新社. 1999. pp. 1, 4, 14. ISBN 4-12-101491-X. OCLC 675273046.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & Co. p. 234,240. ISBN 9781854095237.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen. Samurai Invasion. London: Cassell & Co., p. 120.

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen. Samurai Invasion. London: Cassell & Co., p. 232.

- ^ Berry, Mary Elizabeth. Hideyoshi. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, pp. 127–128.

- ^ a b c Mizuno Goki (2013). "前田利家の死と石田三成襲撃事件" [Death of Toshiie Maeda and attack on Mitsunari Ishida]. 政治経済史学 (in Japanese) (557号): 1–27.

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). "豊臣七将の石田三成襲撃事件―歴史認識形成のメカニズムとその陥穽―" [Seven Toyotomi Generals' Attack on Ishida Mitsunari - Mechanism of formation of historical perception and its downfall]. 日本研究 (in Japanese) (22集).

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). "徳川家康の人情と決断―三成"隠匿"の顚末とその意義―" [Tokugawa Ieyasu's humanity and decisions - The story of Mitsunari's "concealment" and its significance]. 大日光 (70号).

- ^ "七将に襲撃された石田三成が徳川家康に助けを求めたというのは誤りだった". yahoo.co.jp/expert/articles/ (in Japanese). 渡邊大門 無断転載を禁じます。 © LY Corporation. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Mizuno Goki (2016). "石田三成襲撃事件の真相とは". In Watanabe Daimon (ed.). 戦国史の俗説を覆す [What is the truth behind the Ishida Mitsunari attack?] (in Japanese). 柏書房.

- ^ 歴代文化皇國史大觀 [Overview of history of past cultural empires] (in Japanese). Japan: Oriental Cultural Association. 1934. p. 592. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b 竹鼻町史編集委員会 (1999). 竹鼻の歴史 [Takehana] (in Japanese). Takehana Town History Publication Committee. pp. 30–31.

- ^ 尾西市史 通史編 · Volume 1 [Onishi City History Complete history · Volume 1] (in Japanese). 尾西市役所. 1998. p. 242. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ 参謀本部 (1911), "石川貞清三成ノ陣ニ赴ク", 日本戦史. 関原役 [Japanese military history], 元真社

- ^ Mitsutoshi Takayanagi (1964). 新訂寛政重修諸家譜 6 (in Japanese). 八木書店. ISBN 978-4-7971-0210-9. Retrieved 16 May 2024.

- ^ "Masanori + Krokorok - Pokémon Conquest characters". Pokémon. Retrieved 2012-06-17.

- ^ "The Most Expensive Sword in the World - $100 Million Samurai Tachi". World Art News. 5 November 2021. Retrieved 26 March 2024.

External links

[edit]- Biography of Fukushima Masanori (in Japanese)