Nganasan people

ӈәнә"са (нә"), ня" | |

|---|---|

Nganasans, 1927 | |

| Total population | |

| c. 978 (2002) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 834 (2002) | |

| 44 (2001)[1] | |

| Languages | |

| Nganasan language, Russian language | |

| Religion | |

| Animism, Shamanism, Orthodox Christianity | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Selkups, Enets, Nenets, other Uralic peoples | |

The Nganasans (/əŋˈɡænəsæn/ əng-GAN-ə-san; Nganasan: ӈәнә"са(нә") ŋənəhsa(nəh), ня(") ńæh) are a Uralic people of the Samoyedic branch native to the Taymyr Peninsula in north Siberia. In the Russian Federation, they are recognized as one of the indigenous peoples of the Russian North. They reside primarily in the settlements of Ust-Avam, Volochanka, and Novaya in the Taymyrsky Dolgano-Nenetsky District of Krasnoyarsk Krai, with smaller populations residing in the towns of Dudinka and Norilsk as well.[2]

The Nganasans are thought to be the direct descendants of proto-Uralic peoples.[3] However there is some evidence that they absorbed a local Paleo-Siberian population. The Nganasans were traditionally a semi-nomadic people whose main form of subsistence was wild reindeer hunting, in contrast to the Nenets, who herded reindeer. Beginning in the early 17th century, the Nganasans were subjected to the yasak system of Czarist Russia. They lived relatively independently, until the 1970s, when they were settled in the villages they live in today, which are at the southern edges of the Nganasans' historical nomadic routes.

There is no certainty as to the exact number of Nganasans living in Russia today. The 2002 Russian census counted 862 Nganasans living in Russia, 766 of whom lived in the former Taymyr Autonomous Okrug.[4] However, those who study the Nganasan estimate their population to comprise approximately 1,000 people.[a] Historically, the Nganasan language and a Taymyr Pidgin Russian[8] were the only languages spoken among the Nganasan, but with increased education and village settlement, Russian has become the first language of many Nganasans. Some Nganasans live in villages with a Dolgan majority, such as Ust-Avam. The Nganasan language is considered seriously endangered and it is estimated that at most 500 of the Nganasan can still speak it, with very limited proficiency among those 18 and younger.[9]

Etymology

[edit]

The Nganasans first referred to themselves in Russian as Samoyeds, but they would also often use this term when referring to the Enets people and instead refer to themselves as the Avam people. For the Nganasans, the term signified ngano-nganasana, which means 'real people' in the Nganasan language, and referred to both themselves and the neighboring Madu Enets. However, in their own language, the Avam Nganasans refer to themselves as nya-tansa, which translates as 'comrade tribe', whereas the Vadeyev Nganasans to the east prefer to refer to themselves as a'sa which means 'brother', but also includes the Evenks and Dolgan. The Nganasans were also formerly called Tavgi Samoyeds or Tavgis initially by the Russians, which derives from the word tavgy in the Nenets language. Following the Russian Revolution, the Nganasans adopted their current appellation.[10][11]

Geography

[edit]

The Nganasans are the northernmost ethnic group of the Eurasian continent and the Russian Federation, historically inhabiting the tundra of the Taymyr Peninsula. The areas they inhabited stretched over an area of more than 100,000 square kilometers, from the Golchikha River in the west to the Khatanga Bay in the east, and from Lake Taymyr in the north to the Dudypta River in the south.[12] The hunting areas of the Nganasan often coincided with those of the Dolgans and Enets to their east and west respectively. In the winter, they resided in the south of the peninsula at the edge of the Arctic tree line, and during the summer they followed wild reindeer up to 400 miles to the north, sometimes even reaching as far as the Byrranga Mountains.[13]

History

[edit]Origins

[edit]The homeland of the Proto-Uralic peoples, including the Samoyeds, is suggested to be somewhere near the Ob and Yenisey river drainage areas of Central Siberia or near Lake Baikal.[14]

The Nganasan are considered by most ethnographers who study them to have arisen as an ethnic group when Samoyedic peoples migrated to the Taymyr Peninsula from the south, encountering Paleo-Siberian peoples living there who they then assimilated into their culture. One group of Samoyedic people intermarried with Paleo-Siberian peoples living between the Taz and Yenisei rivers, forming a group that the Soviet ethnographer B. O. Dolgikh refers to as the Samoyed-Ravens. Another group intermarried with the Paleo-Siberian inhabitants of the Pyasina River and formed another group which he called the Samoyed-Eagles. Subsequently, a group of Tungusic people migrated to the region near Lake Pyasino and the Avam River, where they were absorbed into Samoyed culture, forming a new group called the Tidiris. There was another group of Tungusic peoples called the Tavgs who lived along the basins of the Khatanga and Anabar rivers and came into contact with the aforementioned Samoyedic peoples, absorbing their language and creating their own Tavg Samoyedic dialect.[15] It is known that the ancestors of the Nganasan previously inhabited territory further south from a book in the city Mangazeya that lists yasak (fur tribute) payments by the Nganasan which were made in sable, an animal that does not inhabit the tundra where the Nganasan now live.[10]

By the middle of the 17th century, Tungusic peoples began to push the Samoyedic peoples northward towards the tundra Taymyr Peninsula, where they merged into one tribe called Avam Nganasans. As the Tavgs were the largest Samoyedic group at the time of this merger, their dialect formed the basis of the present-day Nganasan language. In the late 19th century, a Tungusic group called the Vanyadyrs also moved to the Eastern Taymyr peninsula, where they were absorbed by the Avam Nganasans, resulting in the tribe that is now called Vadeyev Nganasans. In the 19th century, a member of the Dolgans, a Turkic people who lived east of the Nganasans, was also absorbed by the Nganasans, and his descendants formed an eponymous clan, which today, though linguistically fully Samoyedic, is still acknowledged as being Dolgan in origin.[16]

Contact with Russians

[edit]The Nganasans first came into contact with Russians sometime in the early 17th century,[10] and after some resistance, began to pay tribute to the Czar in the form of sable fur under the yasak system in 1618.[17] Tribute collectors established themselves at the "Avam Winter Quarters", at the confluence of the Avam and Dudypta rivers, which is the site of the modern-day settlement Ust-Avam. The Nganasans often tried to avoid paying yasak by changing the names that they provided to the Russians.[18] Relations between the Russians and Nganasans were not always peaceful. In 1666, the Nganasans ambushed and killed yasak collectors, soldiers, tradesmen, and their interpreters on three occasions, stealing the sable furs and property belonging to them. Over the course of the year, 35 men were killed in total.[19]

The Nganasan had little direct contact with merchants and, unlike most indigenous Siberians, they were never baptized[10] or otherwise contacted by missionaries.[20] Some Nganasans traded directly with the Russians, while others did so via the Dolgans.[13] They usually exchanged sable furs for alcohol, tobacco, tea, and various tools, products which quickly integrated themselves into Nganasan culture.[21] In the 1830s,[22] and again from 1907 to 1908, Russian contact caused major smallpox outbreaks among the Ngansans.[23]

Soviet Union

[edit]The Nganasans first came into contact with the Soviets around in the 1930s, when the government instituted a program of collectivization. The Soviets had established that 11% of families owned 60 percent of the deer, while the lower 66% owned only 17 percent,[24] and redistributed this property by collectivizing reindeer into kolkhoz around which the Nganasan then settled.[25] This represented a great change in lifestyle, as the Nganasan, who had primarily been reindeer hunters, were forced to expand their small stock of domesticated reindeer that had previously only been primarily for transport or eaten during periods of famine.[26] Additionally, the Soviets took a greater interest in the Nganasans as a people, and starting in the 1930s, ethnographers began to study their customs.

Despite collectivization and the institution of the kolkhoz, the Nganasans were able to maintain a semi-nomadic lifestyle following domesticated reindeer herds up until the early 1970s, when the state settled the Nganasans along with the Dolgans and Enets in three different villages it constructed: Ust-Avam, Volochanka, and Novaya.[27] Nganasan kolkhoz were combined to create the villages, and after settling in them, the Nganasans shifted from kolkhoz employment to working for gospromkhoz Taymirsky, the government hunting enterprise, which supplied meat to the burgeoning industrial center Norilsk to the southwest. By 1978, all domestic reindeer herding had ceased, and with new Soviet equipment, the yield of hunted wild reindeer reached 50,000 in the 1980s. Most Nganasan men were employed as hunters, and the women worked as teachers or as seamstresses decorating reindeer boots.[27] Nganasan children began schooling in Russian, and even pursuing secondary education. The Soviet planned economy provided the Nganasan settlements with wages, machinery, consumer goods, and education, allowing the Nganasans to achieve a relatively high standard of living by the end of the 1980s.[28]

Religion

[edit]The traditional religion of the Nganasans is animistic and shamanistic. Their religion is a particularly well-preserved example of Siberian shamanism, which remained relatively free of foreign influence due to the Nganasans' geographic isolation until recent history. Because of their isolation, shamanism was a living phenomenon in the lives of the Nganasans, even into the beginning of the 20th century.[29] The last notable Nganasan shaman's seances were recorded on film by anthropologists in the 1970s.[29]

Language

[edit]The Nganasan language (formerly called тавгийский, tavgiysky, or тавгийско-самоедский, tavgiysko-samoyedsky in Russian; from the ethnonym тавги, tavgi) is a moribund Samoyedic language spoken by the Nganasan people. It is now considered highly endangered, as most Nganasan people now speak Russian rather than their native language. In 2010, it was estimated that only 125 Nganasan people can speak it in the southwestern and central parts of the Taymyr Peninsula.[citation needed]

Genetics

[edit]

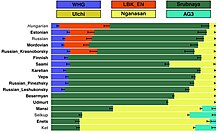

The characteristic genetic marker of the Nganasans and most other Uralic-speakers is Y-DNA haplogroup N1c-Tat. Other Samoyedic peoples mainly have more N1b-P43, rather than N1c, suggesting a bottleneck event.[31] Haplogroup N originated in the northern part of China in 20,000–25,000 years BP[32] and spread to Northern Eurasia, through Siberia to Northern Europe. Subgroup N1c1 is frequently seen in non-Samoyedic peoples, N1c2 in Samoyedic peoples. In addition, mtDNA haplogroup Z, found with low frequency in Saami, Finns, and Siberians, is related to the migration of people speaking Uralic languages.

Nganasans are linked to "Neo-Siberian" ancestry, which is estimated to have expanded from the northeast Asian region into Siberia about ~11,000 years ago BCE.[33]

In 2019, a study based on genetics, archaeology and linguistics found that Uralic speakers arrived in the Baltic region from the East, specifically from Siberia, at the beginning of the Iron Age some 2,500 years ago, together with a Nganasan-related component, possibly linked to the spread of Uralic languages.[34]

In another genetic study in 2019, published in Nature Communications, it was found that the Nganasans best represent a possible source population for the Proto-Uralic people. Nganasan-like ancestry is found in every group of modern Uralic-speakers in varying degrees.[3]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b State statistics committee of Ukraine - National composition of population, 2001 census (Ukrainian)

- ^ Ziker

- ^ a b Lamnidis, Thiseas C.; Majander, Kerttu; Jeong, Choongwon; Salmela, Elina; Wessman, Anna; Moiseyev, Vyacheslav; Khartanovich, Valery; Balanovsky, Oleg; Ongyerth, Matthias; Weihmann, Antje; Sajantila, Antti (27 November 2018). "Ancient Fennoscandian genomes reveal origin and spread of Siberian ancestry in Europe". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 5018. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.5018L. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-07483-5. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6258758. PMID 30479341.

- ^ "Центральная База Статистических Данных". Archived from the original on 12 April 2008.

- ^ Ziker (1998)

- ^ Ziker (2002)

- ^ Ziker (2010)

- ^ Stern (2005)

- ^ Janhunen, Juha. http://www.helsinki.fi/~tasalmin/nasia_report.html#Nganasan

- ^ a b c d Popov (1966), p. 11

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), p. 226

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), p. 230

- ^ a b Stern (2005), p. 290

- ^ Janhunen, Juha (2009). "Proto-Uralic—what, where and when?" (PDF). In Jussi Ylikoski (ed.). The Quasquicentennial of the Finno-Ugrian Society. Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia 258. Helsinki: Société Finno-Ougrienne. ISBN 978-952-5667-11-0. ISSN 0355-0230.

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), pp. 290–292

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), pp. 291–292

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), p. 244

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), p. 245

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), p. 247

- ^ Stern (2005), p. 293

- ^ "The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire". Archived from the original on 26 September 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2012.

- ^ Forsyth (1994), pp. 177–178

- ^ Dolgikh (1962), p. 248

- ^ Chard (1963), p. 113

- ^ Ziker (2002), p. 208

- ^ Johnson & Earle (2000), pp. 118–119

- ^ a b Ziker (2002), p. 209

- ^ Ziker (1998), p. 195

- ^ a b Hajdú, Péter (1975). Uráli népek: Nyelvrokonaink kultúrája és hagyományai (in Hungarian). Budapest: Corvina. ISBN 978-963-13-0900-3. OCLC 3220067.

- ^ Jeong, Choongwon; Balanovsky, Oleg; Lukianova, Elena; Kahbatkyzy, Nurzhibek; Flegontov, Pavel; Zaporozhchenko, Valery; Immel, Alexander; Wang, Chuan-Chao; Ixan, Olzhas; Khussainova, Elmira; Bekmanov, Bakhytzhan; Zaibert, Victor; Lavryashina, Maria; Pocheshkhova, Elvira; Yusupov, Yuldash (June 2019). "The genetic history of admixture across inner Eurasia". Nature Ecology & Evolution. 3 (6): 966–976. doi:10.1038/s41559-019-0878-2. ISSN 2397-334X. PMC 6542712. PMID 31036896.

- ^ Tambets, Kristiina; Rootsi, Siiri; Kivisild, Toomas; Help, Hela; Serk, Piia; Loogväli, Eva-Liis; Tolk, Helle-Viivi; et al. (2004). "The Western and Eastern Roots of the Saami—the Story of Genetic 'Outliers' Told by Mitochondrial DNA and Y Chromosomes". The American Journal of Human Genetics. 74 (4): 661–682. doi:10.1086/383203. PMC 1181943. PMID 15024688.

- ^ Shi, H.; Qi, X.; Zhong, H.; Peng, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. (2013). "Genetic evidence of an East Asian origin and Paleolithic northward migration of Y-chromosome haplogroup N". PLoS One. 8 (6): e66102. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...866102S. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0066102. PMC 3688714. PMID 23840409.

- ^ Sikora, Martin; Pitulko, Vladimir V.; Sousa, Vitor C.; Allentoft, Morten E.; Vinner, Lasse; Rasmussen, Simon; Margaryan, Ashot; de Barros Damgaard, Peter; de la Fuente, Constanza; Renaud, Gabriel; Yang, Melinda A.; Fu, Qiaomei; Dupanloup, Isabelle; Giampoudakis, Konstantinos; Nogués-Bravo, David (June 2019). "The population history of northeastern Siberia since the Pleistocene". Nature. 570 (7760): 182–188. Bibcode:2019Natur.570..182S. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1279-z. hdl:1887/3198847. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31168093. S2CID 174809069.

... the Neosiberian turnover from the south ... largely replaced Ancient Paleosiberian ancestry .... Therefore, this phase of the Neosiberian population turnover must initially have transmitted other languages or language families into Siberia, including possibly Uralic and Yukaghir.

- ^ Saag, Lehti; Laneman, Margot; Varul, Liivi; Lang, Valter; Metspal, Mait; Tambets, Kristiina (May 2019). "The Arrival of Siberian Ancestry Connecting the Eastern Baltic to Uralic Speakers further East". Current Biology. 29 (10): 1701–1711.e16. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2019.04.026. PMC 6544527. PMID 31080083.

Bibliography

[edit]- Chard, Chester S. (1963). "The Nganasan: wild reindeer hunters of the Taimyr Peninsula". Arctic Anthropology. 1 (2): 105–121. JSTOR 40315565.

- Dolgikh, B. O. (1962). "On the Origin of the Nganasans". Studies in Siberian Ethnogenesis. University of Toronto Press.

- Forsyth, James (1994). A History of the Peoples of Siberia: Russia's North Asian Colony 1581–1990. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521477710.

- Johnson, Allen W.; Earle, Timothy K. (2000). The Evolution of Human Societies: From Foraging Group to Agrarian State (2nd ed.). Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804740326.

- Popov, A. A. (1966). The Nganasan: The Material Culture of the Tavgi Samoyeds. Bloomington: Indiana University Publications.

- Stern, Dieter (2005). "Taimyr Pidgin Russian (Govorka)". Russian Linguistics. 29 (3): 289–318. doi:10.1007/s11185-005-8376-3. S2CID 170580775.

- Ziker, John (1998). "Kinship and exchange among the Dolgan and Nganasan of Northern Siberia". In Barry L. Isaac (ed.). Research in Economic Anthropology. Vol. 19. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group. ISBN 978-0-7623-0446-2.

- Ziker, John (2002). "Land use and economic change among the Dolgan and the Nganasan". People and the Land: Pathways to Reform in Post Soviet Siberia (PDF). Dietrich Reimer Verlag.

- Ziker, John (2010). "Changing gender roles and economies in Taimyr". Anthropology of East Europe Review. 28 (2): 102–119.

External links

[edit]- Helimski, Eugene. "Nganasan shamanistic tradition: observation and hypotheses". Shamanhood: The Endangered Language of Ritual, conference at the Centre for Advanced Study, 19–23 June 1999, Oslo. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008.

- Helimski, Eugene (1997). "Factors of Russianization in Siberia and Linguo-ecological Strategies". Northern Minority Languages: Problems of Survival (PDF). "Senri Ethnological Studies" series. Vol. 44. Osaka: Minpaku: National Museum of Ethnology. pp. 77–91.

- Kolga, Margus; et al. (1993). "Nganasans". The Red Book of the Peoples of the Russian Empire. Archived from the original on 26 September 2011.

- Lintrop, Aado. "The Nganasan Shamans from Kosterkin family". Studies in Siberian Shamanism and Religions of the Ugric-Samoyedic Peoples. Folk Belief and Media Group of the Estonian Literary Museum.

- Lintrop, Aado (December 1996). "The Incantations of Tubyaku Kosterkin". Electronic Journal of Folklore. 2: 9–28. doi:10.7592/FEJF1996.02.tubinc. ISSN 1406-0949.

- "Nganasan Clean Tent Rite".

- Trailer for the Russian film People of Taimyr (ЛЮДИ ТАЙМЫРА), via YouTube

- Russian documentary Taboo: The Last Shaman (Табу Последний Шаман), via YouTube