Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb

| Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | The Collective |

| Publisher(s) | LucasArts |

| Director(s) | Richard Hare |

| Producer(s) | Rick Watters Jim Tso |

| Designer(s) | Brad Santos |

| Programmer(s) | Robert Mobbs Nathan Hunt Jason King |

| Artist(s) | Brian Horton |

| Writer(s) | Brad Santos[4] |

| Composer(s) | Clint Bajakian |

| Platform(s) | Xbox, Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 2, OS X |

| Release | XboxMicrosoft WindowsPlayStation 2OS X

|

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

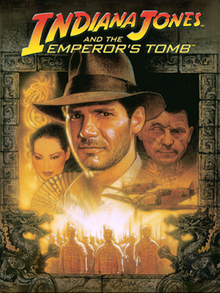

Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb is a 2003 action-adventure video game developed by The Collective and published by LucasArts for the Xbox, Microsoft Windows, PlayStation 2 and OS X. It features cover art by Drew Struzan. The game is an adventure of fictional archeologist Indiana Jones. The story takes place in 1935, acting as a prequel to Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. The tomb mentioned in the title is that of China's first Emperor Qin Shi Huang.

The game had a mixed reception from critics. It was praised for successfully recreating the spirit of the films, but criticised for its camera controls and graphical issues. In March 2015, the game was re-released digitally through GOG.com,[5] and in November 2018, the game was released through Steam.[6][7]

Gameplay

[edit]Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb is an action-adventure game.[8] It is played from a third-person perspective, and takes place across 10 levels. As Indiana Jones, the player can run, jump, climb, and swim. Numerous enemies appear throughout the game, including Nazi guards. The player has a variety of defensive moves, such as punching and kicking. Various guns can be used throughout the game as well, and the player can also use improvised weapons, such as the legs from broken chairs and tables.[9][10]

The player is equipped with Jones' bullwhip, which can be used against enemies. The player can also whip certain overhead objects to swing from one platform to another. Other items include a knife, used for cutting through thick vines. On-screen icons alert the player when to use the whip or knife, and when to perform other actions such as pulling switches and planting explosives. The player's health is replenished by drinking from a canteen of water, which can be refilled at certain points in each level.[9][10] Gameplay is the same on each console.[8]

Plot

[edit]In 1935 in the jungles of British Ceylon, Indiana Jones searches for the idol of Kouru Watu. After retrieving the idol, Jones meets a Nazi agent named Albrecht Von Beck who also seeks it. Jones defeats Von Beck's paid South African ivory hunters and escapes while Von Beck is attacked by a giant albino crocodile. Back at school in New York City, Chinese official Marshall Kai Ti-chan and his female assistant Mei-Ying inform Jones of the "Heart of the Dragon," a black pearl buried with the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huangdi. The Heart is said to grant the wielder immense magical power, and Kai wants Jones to retrieve it before it falls into the wrong hands. Mei-Ying breaks open the Ceylon idol to find the first piece of the "Mirror of Dreams" inside, an artifact that will help navigate through the Emperor's Tomb and reveal the entrance to Huangdi's crypt.

Jones flies to the Prague Castle to acquire the second piece of the Mirror, encountering a large number of Gestapo agents. After solving a series of diverse puzzles and battling a superhuman test subject, he obtains the second piece before he is knocked unconscious by Von Beck, who had survived the crocodile attack (albeit hideously scarred and blind in his right eye). Von Beck then takes the two Mirror pieces and orders his subordinates to transport Jones to Istanbul where Von Beck intends to interrogate him. Jones wakes up in a prison cell where Mei-Ying appears and frees him. He is surprised to find that the Nazis, below Istanbul, have uncovered the ruins of Belisarius' sunken city in search for the final piece of the Mirror. Jones makes his way into the ruins and eventually falls into a sunken amphitheatre where he battles the Kraken guarding the final piece. After defeating the beast, Mei-Ying reappears and tells him that Kai is actually the leader of the Black Dragon Triad, the most powerful crime organization in China. Kai had formed an alliance with the Nazis to find the Heart of the Dragon, but when Jones unwittingly secured the first piece of the Mirror, Kai decided to betray the Nazis in order to get the Heart for himself. Mei-Ying teams up with Jones, both unaware that Kai's bodyguards have been listening in on their conversation.

Mei-Ying and Jones go to British Hong Kong in order to infiltrate Kai's fortress. They begin at the Golden Lotus Opera House, where they wait for Wu Han, a character who first appeared in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. When Mei-Ying is abducted by Kai's men, Jones and Wu Han chase the kidnappers down to a dock in a rickshaw, fighting scores of gangsters along the way. Upon arrival, they see Mei-Ying taken into a submarine by Von Beck. The submarine heads to Kai's private island, and Wu Han and Jones follow in a junk.

After infiltrating a Nazi submarine base, Jones spies Von Beck and Kai arguing about their deal. They reach an agreement in which Von Beck can take the Heart to Adolf Hitler when Kai seizes control of China. Disguising himself as a Nazi, Jones makes his way to the peak of Penglai Mountain and the site of Kai's Black Dragon Fortress where he finds Mei-Ying guarded by the Feng twins, Kai's female bodyguards. After defeating them, Jones falls down a heavily booby-trapped shaft into the temple of Kong Tien where he fights evil spirits and finds a magical Chinese boomerang-like weapon called the Pa Cheng, the Dragon's Claw. Eventually Jones finds Kai assembling the Mirror of Dreams and sacrificing Mei-Ying to Kong Tien. Attempting to rescue her, Jones disrupts the ritual, and Kai flees while Mei-Ying is possessed. Jones frees her and together, with the mirror, they venture to the Emperor's Tomb where he uses the mirror to cross various obstacles. He is however separated from Mei-Ying, despite his efforts. When he arrives at the terracotta maze at the end of the tomb, Von Beck chases him into a boring machine bent on getting rid of Jones once and for all. Von Beck is killed when his tank falls down a chasm, and Jones enters a portal to the Netherworld.

After crossing a short Netherworld-version of the Great Wall of China, Jones finally finds Huangdi's crypt and the body of Qin Shi Huangdi. When Jones takes the Heart of the Dragon, the emperor awakens but is nearly instantly killed by the souls of his victims. Unable to control the power of the Heart, Indy collapses while Kai grabs the pearl. Mei-Ying likewise appears to help Jones, but is shortly afterwards seized by Kai's newfound powers. Kai also creates a shield to protect himself and summons a dragon to battle Jones, but Jones uses the Pa Cheng charged with mystical energy to penetrate Kai's shield and destroys the Heart. At the moment Kai loses his powers, spirits of his victims rise and mistake Kai for the first Emperor of China. Jones and Mei-Ying flee as Kai is devoured by the dragon.

Back in Hong Kong, Jones attempts to share some romantic time with Mei-Ying, but Wu Han is quick to remind him that Lao Che has hired them to find the remains of Nurhachi, leading into the opening of Temple of Doom.

Development

[edit]In January 2002, LucasArts announced that its next Indiana Jones video game would be developed by The Collective.[11] Emperor's Tomb uses an enhanced version of the game engine used for Buffy the Vampire Slayer (2002), also developed by The Collective.[12] The game features more action than its predecessor Indiana Jones and the Infernal Machine (1999).[13][14] Among the differences is the use of improvised weapons.[15]

LucasArts employee Hal Barwood offered some suggestions to The Collective over their story choices, as the idea of Nazis roaming China didn't impress him, but The Collective chose to go on their own way, leading Barwood to feel disappointed with the finished product.[16] Abner Ravenwood, Marion Ravenwood's father who has been an unseen character since Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), was going serve as Indy's partner throughout the game, but his inclusion was dropped due to how unwieldy his design proved to be for the game.[17]

In the films, Indiana Jones is portrayed by Harrison Ford, whose likeness is also used in the game,[12] but the character's voice is provided by David Esch.[18] The game's dialogue was written by Brad Santos.[19] The game's instruction manual was designed by Gregory Harsh to resemble a field diary written by Indiana Jones. It includes various references to the franchise.[20] The game's score was composed by Clint Bajakian, utilizing "The Raiders March" by John Williams.

Reception

[edit]| Aggregator | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | PS2 | Xbox | |

| Metacritic | 73/100[21] | 65/100[22] | 73/100[23] |

| Publication | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| PC | PS2 | Xbox | |

| AllGame | |||

| Eurogamer | 7/10[25] | ||

| GameRevolution | B[36] | ||

| GameSpot | 7.2/10[26] | 4.8/10[10] | 6.6/10[27] |

| GameSpy | 68/100[28] | 80/100[29] | 82/100[30] |

| GamesRadar+ | 75%[34] | 92%[35] | |

| GameZone | 8.3/10[31] | 8/10[32] | 8/10[33] |

| IGN | 7.2/10[37] | 6.6/10[38] | 6.1/10[39] |

| X-Play | |||

Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb received "mixed or average reviews" according to review aggregator Metacritic.[21][22][23]

The Xbox and PC versions of the Emperor's Tomb were received well, with critics praising it for recreating the feel of the movies and well-designed gameplay while criticizing bad camera, controls and some graphical issues.[33][37]

Jeff Gerstmann of GameSpot reviewed each version of the game, and wrote that the soundalike voice actor for Harrison Ford "does a convincing enough job" but felt that some of the other voices "don't fare so well". Gerstmann also wrote that while the plot "contains a few twists and double crosses, the game is very thin on storytelling, only breaking into a cutscene to move you from one part of the world to another".[26][10][27] Gerstmann noted various audio and gameplay glitches in the Xbox version.[27] Gerstmann wrote that the PC version contained less graphical and technical problems compared to the Xbox version, but was critical to the PC version's control issues.[26] Reviewing the PlayStation 2 version, Gerstmann noted some graphical issues as severe and said that it pales in comparison to the Xbox version.[10]

In 2017, PC Gamer wrote that the game had held up well over time and stated that despite some issues such as a poor camera and "some frustratingly twitchy jumping", the game "does a superb job of capturing the spirit of the Indiana Jones films".[41] In 2018, PCGamesN included the game on its list of best action-adventure games for PC, writing that while it "has some flaws, such as being unable to save mid-level, Emperor's Tomb earns its place on this list for truly making you feel like Indiana Jones".[42]

References

[edit]- ^ Varanini, Giancarlo (February 13, 2003). "Indy goes gold". GameSpot. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Parker, Sam (March 14, 2003). "Indiana Jones for PC goes gold". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Varanini, Giancarlo (June 16, 2003). "Indiana Jones goes gold". GameSpot. Archived from the original on February 8, 2022. Retrieved March 10, 2021.

- ^ Robert Mobbs (18 February 2004). "Postmortem: The Collective's Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 1 April 2010.

- ^ Hilliard, Kyle (March 19, 2015). "Six Classic LucasArts Titles Arrive On GoG, Including Loom And Indiana Jones And The Emperor's Tomb". Game Informer. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ Walker, John (November 17, 2018). "More LucasArts classics appear on Steam, including Hit The Road, Afterlife and Outlaws". Rock, Paper, Shotgun. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ Horti, Samuel (November 17, 2018). "Seven old-school LucasArts games just popped up on Steam". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Fudge, James (July 18, 2002). "Nate Schaumberg on Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb". GameSpy. Archived from the original on October 8, 2002.

- ^ a b c Marriott, Scott Alan. "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 16, 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Gerstmann, Jeff (June 25, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PS2)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on August 31, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ "Lookout Dr. Jones!". IGN. January 22, 2002. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b Lafferty, Michael (October 7, 2002). "Producer Jim Tso opens the world of Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb". GameZone. Archived from the original on June 28, 2003.

- ^ "Indiana Jones And The Emperor's Tomb". IGN. May 8, 2002. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Bub, Andrew S. (February 25, 2002). "Rick Watters on Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb". GameSpy. Archived from the original on April 1, 2003.

- ^ MacIsaac, Jason. "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb preview". The Electric Playground. Archived from the original on 19 October 2002.

- ^ VTX7, Juaco (August 14, 2019). "Entrevista: Hal Barwood". El Recoveco del Geek. Archived from the original on March 2, 2020.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Verschuere, Giles (April 24, 2003). "The Collective interview". TheRaider.net. Archived from the original on June 25, 2006.

- ^ Rowley, Jim (January 17, 2021). "Will Harrison Ford Voice Indiana Jones In Bethesda's Game?". Screen Rant. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ Buchanan, Levi (April 15, 2004). "On the fly". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on November 16, 2022. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ "Creating Indy's Manual". IGN. February 11, 2003. Archived from the original on October 28, 2021. Retrieved October 14, 2021.

- ^ a b "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PC)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 8, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PS2)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on April 19, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". Metacritic. Archived from the original on September 29, 2015. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Gladstone, Darren (June 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PC)" (PDF). Computer Gaming World. pp. 94–95. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 3, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Reed, Kristan (March 26, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". Eurogamer. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Gerstmann, Jeff (April 1, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PC)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 6, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ a b c Gerstmann, Jeff (February 28, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". GameSpot. Archived from the original on November 8, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Rausch, Allen (April 3, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PC)". GameSpy. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on April 3, 2003.

- ^ Guzman, Hector (June 26, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PS2)". GameSpy. Archived from the original on July 1, 2003.

- ^ Williams, Bryn (February 17, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". GameSpy. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on April 13, 2003.

- ^ Hopper, Steven (April 9, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PC)". GameZone. Archived from the original on April 21, 2003.

- ^ Bedigian, Louis (July 21, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PS2)". GameZone. Archived from the original on August 4, 2003.

- ^ a b Lafferty, Michael (February 26, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". GameZone. Archived from the original on April 11, 2003.

- ^ Dyer, Andy (July 29, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PS2)". GamesRadar. pp. 1–2. Archived from the original on October 23, 2003.

- ^ Curley, Dan (March 28, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". GamesRadar. Archived from the original on April 13, 2003.

- ^ Gee, Brian (March 3, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". Game Revolution. Archived from the original on April 14, 2003.

- ^ a b Butts, Steve (April 2, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PC)". IGN. Archived from the original on July 18, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Perry, Douglass C. (July 2, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (PS2)". IGN. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ Goldstein, Hilary (February 14, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". IGN. Archived from the original on November 19, 2016. Retrieved November 18, 2016.

- ^ D'Aprile, Jason (February 21, 2003). "Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb (Xbox)". Extended Play. Archived from the original on February 21, 2003.

- ^ Kelly, Andy (April 25, 2017). "Feeling like Indiana Jones in The Emperor's Tomb". PC Gamer. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

- ^ "The best action-adventure games on PC". PCGamesN. 2018. Archived from the original on January 10, 2019. Retrieved January 9, 2019.

External links

[edit]- Official website, archived via the Wayback Machine

- Indiana Jones and the Emperor's Tomb at MobyGames

- 2003 video games

- Action-adventure games

- Indiana Jones video games

- MacOS games

- PlayStation 2 games

- Video games scored by Clint Bajakian

- Video game prequels

- Video game interquels

- Video game sequels

- Video games set in China

- Video games set in Hong Kong

- Video games set in Sri Lanka

- Video games set in Turkey

- Video games set in the Czech Republic

- Video games developed in the United States

- Cultural depictions of Qin Shi Huang

- The Collective (company) games

- Aspyr games

- Windows games

- Xbox games

- Video games set in 1935